-

口服给药是最简单的给药方式,药物是否适合口服给药取决于其在胃肠道中的有效吸收,因此,开发能准确预测口服药物吸收的方法对药物研发相关研究具有非常重要的意义。近几十年来,为了评估临床前开发过程中的口服药物吸收,研究人员们已经建立了多种药物肠吸收的研究方法,主要有体外试验法(in vitro)、在体试验法(in situ)和体内试验法(in vivo)等。动物模型可以模拟整个有机体的生理,但动物模型在肠道生理学以及肠道转运蛋白的表达模式和底物特异性方面与人类有很大不同[1]。2004年,美国FDA估计,92%通过动物试验的药物未能进入市场,原因是动物试验没有预测到的有效性和安全性问题。此外,动物模型往往具有伦理学争议。与动物模型相比,体外培养细胞模型具有操作简便、成本低、无伦理问题等优点[2],研究人员开发了Boyden Chamber和Transwell等模型来模拟肠道的复杂结构和功能。然而,传统的体外培养细胞模型通常缺乏体内特性,例如,流体流动、周期性蠕动、宿主与微生物之间的串扰以及组织之间的串扰[3]。随着微制造和3D打印技术的发展,肠芯片(gut-on-a-chip, GOC)为体外研究肠道疾病提供了新方法[4]。基于肠道功能,肠芯片引入了具有不同部件的模块,例如,用于流体流动的注射泵和用于机械变形的压力系统[5],用于模拟一些肠道功能,使其更具生理相关性。肠芯片突破了传统细胞培养和动物实验的局限性,具有体积小、高度集成化和高通量等特点。本文综述了目前国内外肠芯片模型以及与肠道相关的多器官耦合芯片模型的研究进展,介绍了基于微流控芯片的肠道模型在疾病建模、药物吸收和转运方面的应用。

-

肠道是人体重要的消化器官,是从胃幽门至肛门中最长的一段,主要器官功能是进行消化、吸收、分泌和免疫[6]。肠上皮是人体最大的黏膜表面,覆盖约400 m2的表面积,单层细胞组织形成隐窝和绒毛结构[7]。隐窝和绒毛是肠道基本的、具有自我更新功能的结构单位。人体小肠和大肠体内肠隐窝的实际深度分别为135 μm和400 μm,小肠绒毛的高度为600 μm[8]。隐窝和绒毛分别包括干细胞增殖和分化细胞区域。在肠上皮的分化绒毛区域中,发现了3种主要类型的分化肠上皮细胞(IEC):肠上皮细胞、杯状细胞和肠内分泌细胞[9]。肠上皮细胞是肠上皮中最常见的细胞,负责消化和吸收肠腔中的营养物质[10]。杯状细胞分泌的黏液在肠上皮上维持一层连续的黏液,提供保护屏障并有助于润滑肠道内壁[11]。肠内分泌细胞产生多种激素并调节许多不同的功能[12]。

-

肠道屏障是机体内部和外部之间的屏障,允许营养素和液体的吸收,同时阻止有毒、有害物质的侵入,对人体的健康起着重要作用。肠道屏障分为四类:机械屏障、化学屏障、生物屏障和免疫屏障[7]。机械屏障又称为物理屏障,它能有效阻止有害物质,如细菌、毒素等透过肠黏膜进入机体的其他部位造成肠道损伤引发各类疾病,是人体肠道的第一道防线[13]。物理屏障主要通过细胞间的紧密连接复合构成,维持肠上皮细胞的完整性和渗透性[14]。化学屏障由胃肠道各种分泌物包括黏液、胃酸以及各种消化酶、溶菌酶等组成[15-16]。生物屏障是肠黏膜屏障的重要组成部分,由肠道微生物群附着在肠黏膜层上形成的一个动态稳定的微生物屏障[15]。免疫屏障由肠道相关淋巴组织及肠上皮固有层中的免疫细胞组成,如潘氏细胞、巨噬细胞、树突状细胞、淋巴细胞等,可分泌各种抗菌肽、IgG和细胞因子,维持肠道内稳态[17]。

-

药物在胃肠道黏膜上皮细胞的吸收过程是药物在生物膜两侧的跨膜转运过程,药物的跨膜转运方式主要分为被动转运、转运体介导的主动转运和膜动转运等。口服药物在肠道的吸收不仅是简单的被动转运,还通过肠道上皮细胞的药物转运体来实现,其中,转运体参与的主动转运在药物吸收过程中起关键作用[18]。根据底物的转运方向,可以将转运体分为摄入型转运体和外排型转运体两大类,它们控制着肠黏膜屏障的通透性,影响了药物的生物利用度[19]。

为了研究肠道屏障功能及药物吸收特征,研究人员开发了各种体外和离体肠道吸收模型。将细胞外基质(ECM)包被肠上皮细胞置于Transwell培养装置中,常用于研究肠道屏障功能或药物吸收。但这种2D培养模式没有介质流动或施加机械应变,不能再现肠细胞和组织形态或重建其他关键的肠分化功能,肠绒毛无法分化,肠道分泌功能受到抑制[20]。为实现3D肠道细胞模型的建立,研究人员使用不同支架包埋细胞。Li等[21]使用胶原凝胶作为支架,将共培养的Caco-2/HT29-MTX单层细胞和两种基质细胞(成纤维细胞和免疫细胞)合并到胶原凝胶中,与Caco-2细胞的单层培养相比,构建的3D模型显示出更多的生理相关特征。研究表明,使用胶原凝胶作为支架的3D肠道模型可能成为研究肠道内药物转运的有前景的工具。但其也有一定的局限性,在长时间培养过程中,由于胶原蛋白降解,细胞穿透基质形成多层细胞,导致Caco-2细胞在胶原支架上的培养,绒毛高度缩短[22]。另外一些离体模型,如外翻囊模型[23]、Ussing腔模型[24]和InTESTineTM[25]在生理学上高度相关,但这些模型的吞吐量和寿命往往有限(最长可达6~8 h)。

-

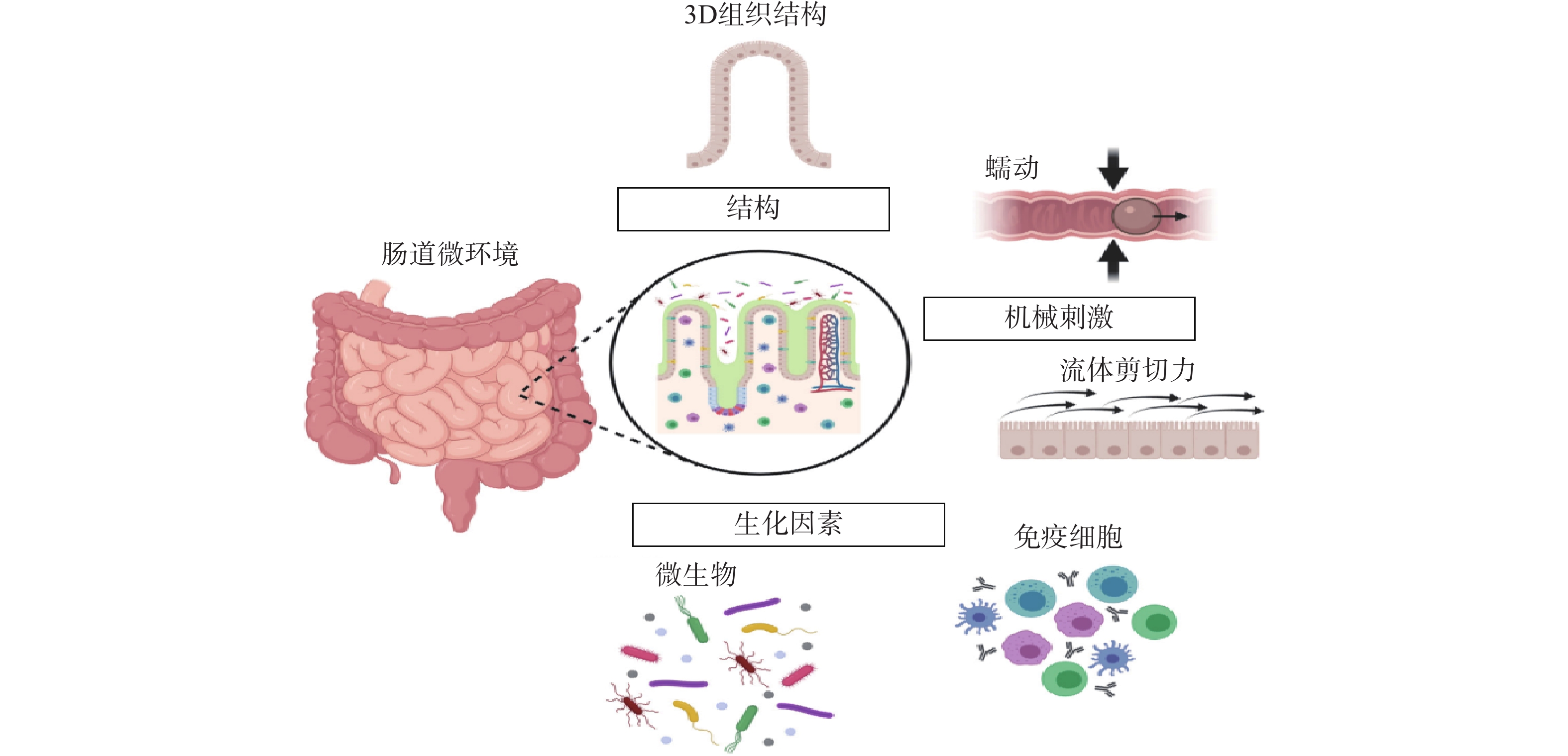

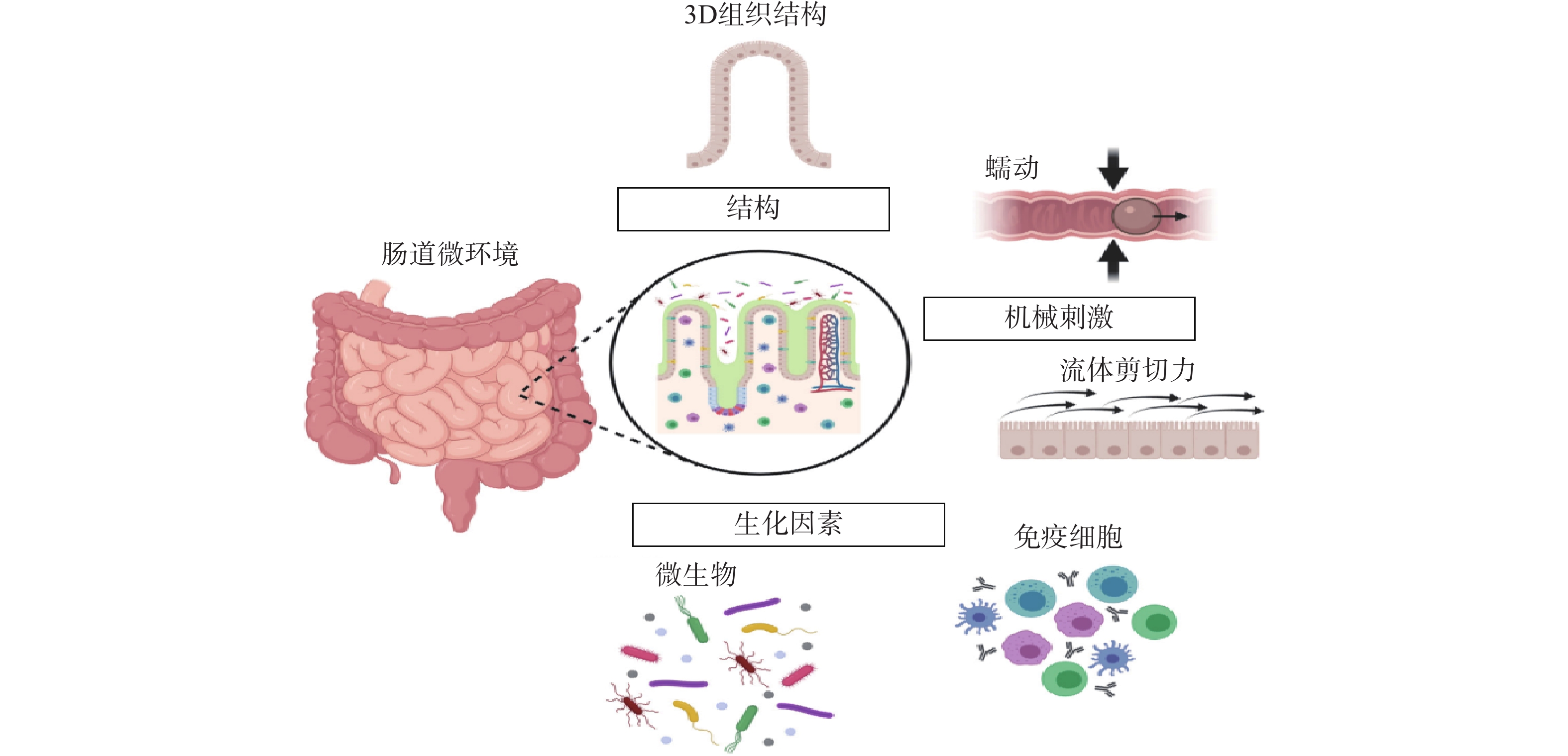

常规的肠道体外模型缺乏对组织结构的真实模拟、缺乏微生物群,以及肠道功能的复杂性,例如蠕动和流动。随着微流控技术的飞速发展,基于微流控的肠芯片成为了模拟人体胃肠道的有效途径。如图1所示,肠道微环境的关键因素包括肠道的3D绒毛结构、蠕动运动和肠屏障功能等[26]。为了真实地模拟人体肠道,肠芯片模型应能实现以下功能:①通过体外拉伸细胞培养膜来模拟蠕动样运动;②通过控制流体来再现肠道复杂的3D绒毛结构;③通过控制微流体的设计结构和材料的渗透性来产生生理氧梯度:④通过多细胞共培养的方式,研究肠道与其他组织或肠道-微生物之间的互作关系。

图 1 肠道微环境关键特征[26]

-

在过去的10年中,肠道芯片平台已经从简单的2D结构发展到包括更全面的功能,例如绒毛结构、肠道蠕动、氧梯度,甚至免疫系统。在肠道器官芯片发展的过程中,肠芯片的类型主要分为两种:二维夹膜肠芯片和三维绒毛肠芯片。

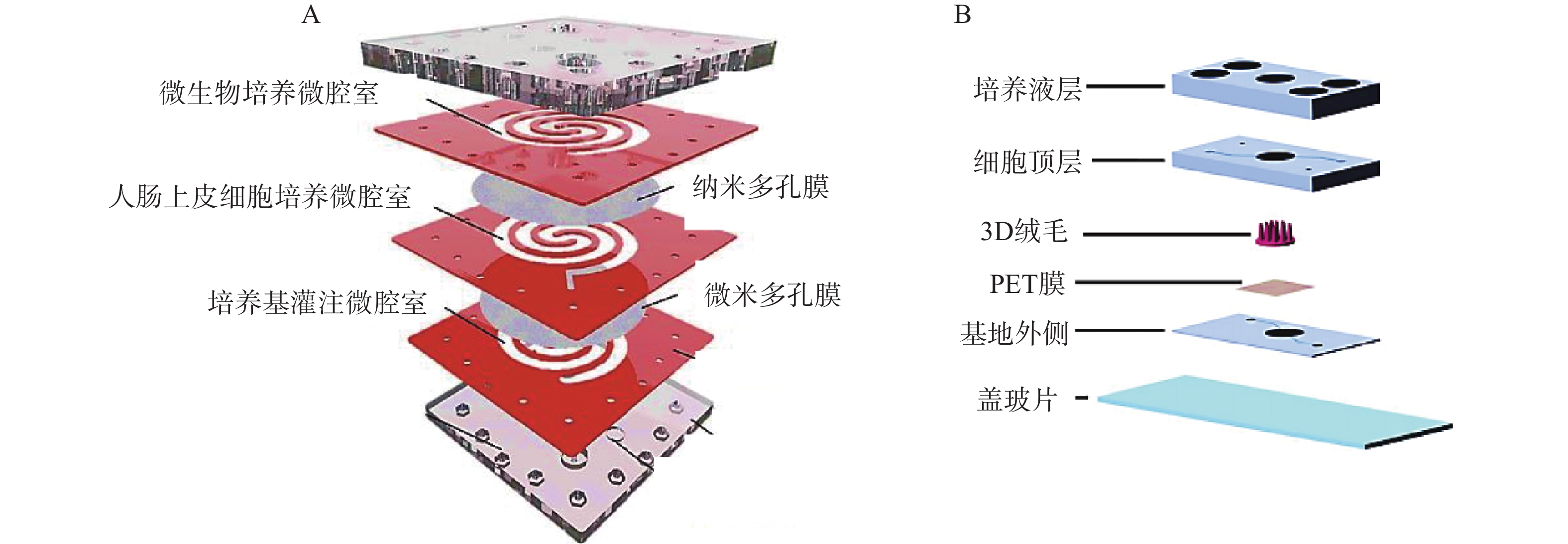

二维夹膜肠芯片最常见的设备结构包含两个通道(上部和下部),由半透膜(例如聚碳酸酯或聚酯材料)隔开,在膜上生长的肠上皮细胞形成单层上皮的顶端和基底外侧,这种简单的2D模型通常用于评估药物和营养吸收的体外药动学特性。Kimura等[27]开发了一种集成泵式循环装置和光学检测功能的微流控模型,该模型由被胶原蛋白涂层的半透膜分隔的两层通道组成,以抗癌药物环磷酰胺的渗透评价其吸收功能。Shah等[28]设计了一种基于微流控芯片的人类-微生物共培养模型“人与微生物交互系统”(HuMiX),见图2。培养基灌注微腔室与人肠上皮细胞培养微腔室之间用微米多孔膜(孔径1 μm)隔开,人肠上皮细胞培养微腔室与微生物培养微腔室之间用纳米多孔膜(孔径50 nm)隔开,每个微腔室有独立的进出口,该模型还集成了光电二极管用于监测溶解氧的浓度。2D肠道芯片模型可以模拟肠道细胞上的流体剪切应力,以减少对细胞和培养基的需求,但该模型仍缺乏模拟肠道组织关键特征的功能。

三维绒毛结构的实现对于构建体外肠道模型至关重要,肠道内的绒毛微结构不仅是肠上皮层的生理屏障,更重要的是增加了肠表面的吸收面积。虽然有报道称在平面基质上自发形成绒毛,但缺乏对绒毛尺寸和分布的控制,而且重复性差。微型3D支架的集成已经成为更好地再现人类肠道结构的解决方案。Shim等[29]植入了胶原蛋白支架,以重现肠道组织三维绒毛结构,绒毛高度为300 μm,绒毛间距为150 μm。3D条件下Caco-2细胞增殖良好,均能形成肠屏障。此外,将细胞置于灌注培养的3D培养条件下,可显著提高细胞的代谢活性。Costello等[30]利用激光雕刻翻模的技术制作了一种肠道芯片,在这种芯片中细胞依附于所制作的绒毛生长;但是激光雕刻在模具的制作中有一定局限性。激光雕刻利用激光垂直切割平面基底,制作出的模型多为柱状结构,较难制作出更为复杂的3D模型。张忆恒等[31]通过3D打印技术与表面微结构转移方法,成功地模拟了更为复杂的肠道绒毛。

-

在肠道中,剪切力在细胞分化中起着重要作用,包括增强黏液产生、增加线粒体活性和提高药物吸收[32]。2D培养时细胞保持在静态条件下,动态参数不容易模拟。在微流控装置中,流体流动可以通过蠕动泵、注射器泵、重力或静水压力以及压力发生器产生,模拟体内液体流动的范围及其在细胞表面的相关剪切应力。与静态条件相比,在连续流动和循环应变下,Caco-2细胞经历细胞分化、极化、绒毛形成、屏障完整性维持、黏液产生等。GOC器件的剪切应力一般取值在0.01 ~ 0.06 dyn/cm2之间,大多数模型中的剪切应力是使用蠕动泵引入的,但这些装置体积庞大且吞吐量低。Tan等[33]用2个微型蠕动泵克服了低吞吐量的限制,每个泵有8个泵管路,允许流体通过16个微通道输送,通过测量微流控芯片中培养的Caco-2细胞氨肽酶活性评估其生长和分化速度,与第21天的静态培养的Transwell系统相比,微流控装置中的Caco-2细胞在第5天显示出更高的氨肽酶活性。尽管该系统具有简单、高通量的特点,但这些模型在重现定义的流速方面是有限的。Kim等[34]开发了一个具有流体流动和施加循环机械应变的肠芯片模型。该装置由两个微通道组成,两侧有两个空心腔室,在空心腔室中施加真空,使分离通道的多孔膜单向延伸。该研究发现,流体流动和周期性机械应变的结合导致了褶皱的形成,这些褶皱再现了肠绒毛的结构,并且该系统中使用的Caco-2细胞显示出极化柱状形态,大小与体内上皮细胞相似。

-

在消化过程中,蠕动是由平滑肌与肠神经系统协同作用,在整个胃肠道内产生的食物的不自主的、周期性的推进。蠕动有助于食物消化、营养吸收和肠排空,但也对上皮产生剪切力和径向压力。研究表明,机械拉伸对于准确模拟人体肠道生理、允许细胞分化和防止细菌过度生长至关重要[35]。Jing等[36]提出并构建了一种基于循环变化流体压差原理的新型蠕动肠模型,通过使用多通道、计算机控制的气动泵同时实现了肠道微系统的流体流动和蠕动,考察了蠕动和流体流动对该装置肠上皮细胞生长和分化的影响。结果表明,微流体装置中的周期性蠕动加上流体流动显著促进了肠上皮细胞的增殖以及糖萼和微绒毛的分泌。此外,肠上皮细胞的屏障、吸收和代谢功能以及细胞分化也受到芯片上周期性蠕动和流体流动的影响。Fang等[37]开发另一款包含200个依次连接的横向微孔阵列芯片,通过调节微孔周围的气道内部气压,从而实现孔内类器官的周期性收缩与舒张,模拟肠道的蠕动。研究结果发现,在蠕动环境中长成的人结肠肿瘤类器官具有更均匀的尺寸分布,对该纳米胶束的摄入量显著降低。Grassart等[38]通过循环拉伸模拟肠道蠕动,研究蠕动状态是否会影响人类志贺菌在3D结肠上皮内的传染性。研究表明,与非机械刺激条件相比,拉伸力(蠕动)的应用显著提高了约50%的感染率,蠕动运动促进了细菌入侵。

-

肠上皮富含含氧血液,对于增强绒毛的营养吸收和加速针对病原体的免疫反应至关重要。人体肠道是多种微生物群落的宿主,肠道微生物群在肠道的消化和吸收功能中发挥着重要作用[39]。HuMiX实现了肠道模型中氧气浓度梯度的变化,允许Caco-2细胞和厌氧菌之间的共培养,在体内重现转录、代谢和免疫特征[28]。Shin等[40]开发了一种缺氧-氧气接口(AOI芯片),将缺氧培养基从细菌生长的上通道灌注到肠细胞生长的下通道。实验结果表明,上皮细胞层的存在和管腔微通道中的流量依赖性调节对于在AOI芯片中产生稳态垂直氧梯度是必要且充分的。另一个包含高分辨率溶解氧监测的GOC模型是肠芯片,它有6个传感器盘,在模型的顶部和底部固定有氧淬灭荧光颗粒,允许实时监测氧水平。这种GOC模型有一个中央厌氧室,经常用饱和的5% CO2冲洗,维持上腔内低氧水平。使用这款厌氧肠道芯片,Jalili-Firoozinezhad等[41]也证明厌氧条件比好氧条件在生理上能保持更高的微生物多样性。表1概括了常见的肠道吸收芯片模型及其应用。

表 1 肠芯片模型的主要组成和应用

细胞类型 共培养 膜材料 细胞外基质 剪切力 蠕动

(循环机械应变)氧气梯度 应用 Caco-2 否 聚对苯二甲酸(PET)膜 无 1 μl/h 否 否 肠道吸收的功能[42] Caco-2 鼠李糖乳杆菌GG (LGG) 聚碳酸酯(PC)膜 胶原蛋白 25 μl/h 否 是 宿主-微生物分子相互作用[28] Caco-2 人肠微血管内皮细胞 (HIMEC) 聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 否 是 概述疾病模型和对策药物筛选[41] Caco-2 LGG PDMS多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道的运输,吸收和毒性研究[34] Caco-2 大肠杆菌 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道-微生物相互作用和疾病模拟[35] Caco-2 人脐静脉内皮细胞 (HUVEC)、大肠杆菌细胞和巨噬细胞 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白 60 μl/h 15%;0.17 Hz 否 模拟肠道炎症模型和药物筛选[43] 肠道活检类器官 HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 模拟正常肠道生理学[44] 人十二指肠类器官(成人供体) HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物(上皮侧)、Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和纤连蛋白混合物(血管侧) 30 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 研究肠道代谢和药物转运[45] Caco-2 否 无 聚乙烯-醋酸乙

烯酯0.1 ml/min 否 否 高通量药物吸收分析和细菌-宿主相互作用的研究[30] -

肠炎是一种在发达国家和发展中国家都具有高发病率的疾病,炎症性肠病(IBD)已成为全球性问题,主要包括溃疡性结肠炎和克罗恩病两大类。研究人员发现通过添加细胞因子混合物,例如,白介素-1β、肿瘤坏死因子-α和干扰素γ[46-47],或通过与外周血单核细胞共培养可以在体外模拟肠道炎症[35]。

Kim等[35]在肠芯片中引入致病性大肠杆菌和人单核巨噬细胞构建了相应的肠炎病理模型,并且观察到黏液层损伤、屏障损伤及炎性因子大量表达等炎症反应。之后Shin等[48]又通过在肠腔引入葡聚糖硫酸钠(DSS),首次在体外构建了DSS肠炎损伤及恢复模型,利用该模型作者证明了氧化应激反应是炎症损伤的前提。研究发现蠕动的微流体模型可以重现在小鼠模型中相应的结肠炎,并能观察到的屏障完整性和绒毛结构的破坏。使用来自致病性大肠杆菌的脂多糖激活单核细胞,Caco-2细胞被诱导分泌促炎细胞因子,进而损害屏障完整性,从而模仿IBD病理学特征。此外,促炎信号可以促进中性粒细胞的募集,从而进一步加剧肠道损伤。重要的是,研究人员发现DSS暴露前给予益生菌可以维持肠道屏障,而在DSS后添加细菌时,肠道屏障功能会丧失[49]。这些结果表明,利用体外肠芯片建立肠炎病理模型,可以为肠炎病理机制研究及其治疗药物筛选提供更接近体内肠道环境的研究平台。

-

与传统体外肠道模型相比,肠芯片具有高度还原人体肠道微环境、连续的液体流动和高通量筛选的优势[50]。Imura等[42]开发了一种基于微流控芯片的模拟肠道的系统,该芯片由载玻片、半透膜和PDMS组成。以荧光测定结果评价药物渗透性试验,结果显示环磷酰胺能渗透肠屏障,其渗透系数较高,而路西法黄不能在肠壁吸收,其渗透系数较低。这些结果与传统方法的结果一致,证明了该款芯片评估药物吸收的可行性。

Kulthong等[51]分别使用传统的Transwell(静态)和肠芯片(动态)模型,比较高渗透性化合物(安替比林、酮洛芬和地高辛)和低渗透性化合物(阿莫西林)的转运,并使用HPLC或LC-MS测定这些化合物在静态和动态条件下的转运结果。结果显示,相对于静态条件,肠芯片的药物摄取较低,其渗透性值与生物制药分类系(BCS)一致。同样,在接种Caco-2细胞的微流体装置中,几种化合物(姜黄素、甘露醇、葡聚糖、咖啡因和阿替洛尔)的吸收率与体内吸收的研究数据相当。

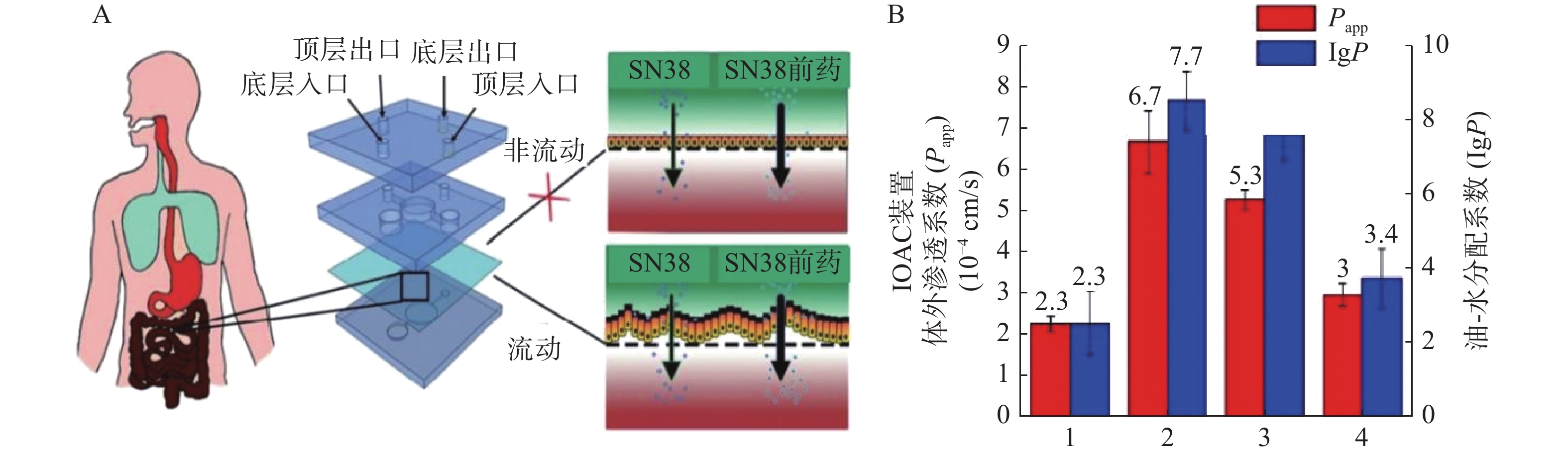

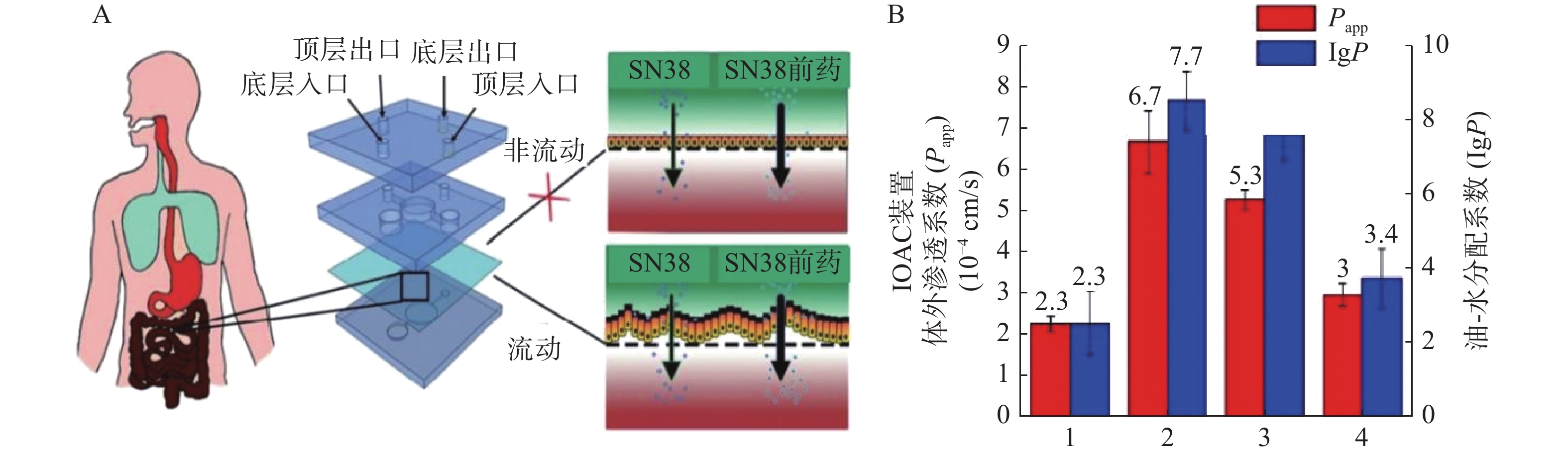

抗癌药物7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱(SN-38)是伊立替康经羧酸酶转换后的活性代谢物,其抑制拓扑酶Ⅰ的活性远大于伊立替康,但其具有低水溶性和低跨黏膜通透性的缺点。研究人员发现将其合成为亲脂性前体药物能解决低口服生物利用度问题。Pocock等[52]开发了一款基于微流体的肠道芯片(IOAC)模型,该模型可用于研究亲脂性前药的结构-渗透性的关系(见图3)。IOAC模型利用外部机械力作用,诱导上皮细胞单层产生特异性分化,使细胞表面呈现微绒毛表达起伏形态的屏障功能,这比传统的Transwell模型更具生物相似性。用不同链长和不同分子位置的脂肪酸酯修饰SN-38,观察到SN-38前药溶解度与渗透性系数之间有良好的相关性。论证了模仿肠道上皮关键特征的IOAC 模型在筛选亲脂性前药方面具有显著潜力[52]。

图 3 IOAC装置及对难溶SN38和前药的体外渗透系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较[52]

-

近年来,肠道芯片模型在芯片设计、微环境、微流体操控和细胞培养技术方面已经取得了重大进展,为胃肠道疾病机制研究和个体化治疗的发展提供了新的模型。但该技术本身仍然面临许多挑战。

肠上皮细胞的来源对于肠芯片的研究至关重要,Caco-2是目前应用最广泛的模拟肠上皮屏障的细胞系,但Caco-2细胞缺乏黏液生成层,很难控制其分化[53]。此外,Caco-2细胞表现出与人类肠道组织不同的转运蛋白表达[54]。因此,肠芯片还需要进一步研究,以确保上皮细胞系的代谢和转运蛋白活性与在体内观察到的相似。尽管微流控肠芯片模型模拟了人类肠道的许多不同表型和反应,但缺乏在某些疾病中发挥重要作用的特征。例如,平滑肌细胞表达Toll样受体,并且可以通过调节神经胶质源性神经营养因子的产生来调节神经元的完整性。因此,未来的肠道芯片模型构建中应考虑更多因素,例如肌肉和神经系统细胞[20],使得模型具有更多的肠道特征和功能,更接近真实的生理环境。

肠芯片研究的另一个挑战是材料的选用。尽管PDMS在微流控器官装置制备方面具有明显的优势,但PDMS可能吸附介质中存在的小分子、药物或其他荧光标记物,从而降低溶质分子浓度的重现性[55]。为了克服这一点,PDMS及其替代聚合物(例如聚氨酯、苯乙烯嵌段共聚物)的表面改性或基于ECM的材料更适用于预测药物生物利用度或吸收的研究[20]。目前,水凝胶广泛应用于肠道微流控模型,可以提供类似于体内细胞-细胞外基质相互作用的机械和生化环境,促进类组织结构的形成[55]。但其同时存在一些问题,如不稳定、易降解等。因此在未来的肠芯片研究中,寻找开发更优的PDMS替代材料也是非常有必要的。

Development and application of in vitro intestinal absorption model based on microfluidic chips

-

摘要: 肠道是口服药物吸收的主要部位,肠道的上皮细胞上含有绒毛和微绒毛,它们通过增加表面积等因素促进分泌、细胞黏附和吸收。传统的二维/三维(2D/3D)细胞培养模型、动物模型在研究药物吸收方面发挥了重要作用,但是由于缺乏足够的人体药动学的可预测性或伦理问题等,其应用存在一定局限性。因此,以体外活细胞为基础,模拟人肠道的核心结构和关键功能是构建基于微流控芯片的肠道模型的研究重点。该模型是利用微加工技术制备出的模拟人体肠道的复杂微结构、微环境和生理功能的微流控芯片仿生系统。与2D细胞培养和动物实验相比,肠芯片模型能有效地模拟人体内环境,在药物筛选方面更具特异性。本综述概括了国内外肠芯片模型以及与肠道相关的多器官耦合芯片模型的研究进展,及其在疾病建模、药物吸收和转运方面的应用,并总结了当前肠芯片模拟肠道稳态和疾病面临的挑战,为进一步建立更可靠的体外肠芯片模型提供参考。Abstract: The intestine is the main site of oral drug absorption, and the epithelial cells of the intestine contain villi and microvilli, which promote secretion, cell adhesion, and absorption by increasing surface area and other factors. Traditional two-dimensional/three-dimensional (2D/3D) cell culture models and animal models have played an important role in studying drug absorption, but their application is limited due to the lack of sufficient predictability of human pharmacokinetics or ethical issues, etc. Therefore, mimicking the core structure and key functions of the human intestine based on in vitro live cells has been the focus of research on constructing a microfluidic chip-based intestinal model. The model is a microfluidic chip bionic system that simulates the complex microstructure, microenvironment, and physiological functions of the human intestine using microfabrication technology. Compared with 2D cell culture and animal experiments, the intestinal microarray model can effectively simulate the human in vivo environment and is more specific in drug screening. The research progress and applications in disease modeling, drug absorption and transport of intestinal microarray models and intestine-related multi-organ coupled microarray models at home and abroad were reviewed in this paper. The current challenges of intestinal chip simulating intestinal homeostasis and diseases were summarized, in order to provide reference for the further establishment of a more reliable in vitro intestinal chip model.

-

Key words:

- microfluidic chips /

- intestinal absorption model /

- microenvironment /

- applications

-

口服给药是最简单的给药方式,药物是否适合口服给药取决于其在胃肠道中的有效吸收,因此,开发能准确预测口服药物吸收的方法对药物研发相关研究具有非常重要的意义。近几十年来,为了评估临床前开发过程中的口服药物吸收,研究人员们已经建立了多种药物肠吸收的研究方法,主要有体外试验法(in vitro)、在体试验法(in situ)和体内试验法(in vivo)等。动物模型可以模拟整个有机体的生理,但动物模型在肠道生理学以及肠道转运蛋白的表达模式和底物特异性方面与人类有很大不同[1]。2004年,美国FDA估计,92%通过动物试验的药物未能进入市场,原因是动物试验没有预测到的有效性和安全性问题。此外,动物模型往往具有伦理学争议。与动物模型相比,体外培养细胞模型具有操作简便、成本低、无伦理问题等优点[2],研究人员开发了Boyden Chamber和Transwell等模型来模拟肠道的复杂结构和功能。然而,传统的体外培养细胞模型通常缺乏体内特性,例如,流体流动、周期性蠕动、宿主与微生物之间的串扰以及组织之间的串扰[3]。随着微制造和3D打印技术的发展,肠芯片(gut-on-a-chip, GOC)为体外研究肠道疾病提供了新方法[4]。基于肠道功能,肠芯片引入了具有不同部件的模块,例如,用于流体流动的注射泵和用于机械变形的压力系统[5],用于模拟一些肠道功能,使其更具生理相关性。肠芯片突破了传统细胞培养和动物实验的局限性,具有体积小、高度集成化和高通量等特点。本文综述了目前国内外肠芯片模型以及与肠道相关的多器官耦合芯片模型的研究进展,介绍了基于微流控芯片的肠道模型在疾病建模、药物吸收和转运方面的应用。

1. 肠道基本结构与功能

1.1 小肠的结构

肠道是人体重要的消化器官,是从胃幽门至肛门中最长的一段,主要器官功能是进行消化、吸收、分泌和免疫[6]。肠上皮是人体最大的黏膜表面,覆盖约400 m2的表面积,单层细胞组织形成隐窝和绒毛结构[7]。隐窝和绒毛是肠道基本的、具有自我更新功能的结构单位。人体小肠和大肠体内肠隐窝的实际深度分别为135 μm和400 μm,小肠绒毛的高度为600 μm[8]。隐窝和绒毛分别包括干细胞增殖和分化细胞区域。在肠上皮的分化绒毛区域中,发现了3种主要类型的分化肠上皮细胞(IEC):肠上皮细胞、杯状细胞和肠内分泌细胞[9]。肠上皮细胞是肠上皮中最常见的细胞,负责消化和吸收肠腔中的营养物质[10]。杯状细胞分泌的黏液在肠上皮上维持一层连续的黏液,提供保护屏障并有助于润滑肠道内壁[11]。肠内分泌细胞产生多种激素并调节许多不同的功能[12]。

1.2 肠道屏障

肠道屏障是机体内部和外部之间的屏障,允许营养素和液体的吸收,同时阻止有毒、有害物质的侵入,对人体的健康起着重要作用。肠道屏障分为四类:机械屏障、化学屏障、生物屏障和免疫屏障[7]。机械屏障又称为物理屏障,它能有效阻止有害物质,如细菌、毒素等透过肠黏膜进入机体的其他部位造成肠道损伤引发各类疾病,是人体肠道的第一道防线[13]。物理屏障主要通过细胞间的紧密连接复合构成,维持肠上皮细胞的完整性和渗透性[14]。化学屏障由胃肠道各种分泌物包括黏液、胃酸以及各种消化酶、溶菌酶等组成[15-16]。生物屏障是肠黏膜屏障的重要组成部分,由肠道微生物群附着在肠黏膜层上形成的一个动态稳定的微生物屏障[15]。免疫屏障由肠道相关淋巴组织及肠上皮固有层中的免疫细胞组成,如潘氏细胞、巨噬细胞、树突状细胞、淋巴细胞等,可分泌各种抗菌肽、IgG和细胞因子,维持肠道内稳态[17]。

1.3 肠道吸收和转运与体内外肠道模型

药物在胃肠道黏膜上皮细胞的吸收过程是药物在生物膜两侧的跨膜转运过程,药物的跨膜转运方式主要分为被动转运、转运体介导的主动转运和膜动转运等。口服药物在肠道的吸收不仅是简单的被动转运,还通过肠道上皮细胞的药物转运体来实现,其中,转运体参与的主动转运在药物吸收过程中起关键作用[18]。根据底物的转运方向,可以将转运体分为摄入型转运体和外排型转运体两大类,它们控制着肠黏膜屏障的通透性,影响了药物的生物利用度[19]。

为了研究肠道屏障功能及药物吸收特征,研究人员开发了各种体外和离体肠道吸收模型。将细胞外基质(ECM)包被肠上皮细胞置于Transwell培养装置中,常用于研究肠道屏障功能或药物吸收。但这种2D培养模式没有介质流动或施加机械应变,不能再现肠细胞和组织形态或重建其他关键的肠分化功能,肠绒毛无法分化,肠道分泌功能受到抑制[20]。为实现3D肠道细胞模型的建立,研究人员使用不同支架包埋细胞。Li等[21]使用胶原凝胶作为支架,将共培养的Caco-2/HT29-MTX单层细胞和两种基质细胞(成纤维细胞和免疫细胞)合并到胶原凝胶中,与Caco-2细胞的单层培养相比,构建的3D模型显示出更多的生理相关特征。研究表明,使用胶原凝胶作为支架的3D肠道模型可能成为研究肠道内药物转运的有前景的工具。但其也有一定的局限性,在长时间培养过程中,由于胶原蛋白降解,细胞穿透基质形成多层细胞,导致Caco-2细胞在胶原支架上的培养,绒毛高度缩短[22]。另外一些离体模型,如外翻囊模型[23]、Ussing腔模型[24]和InTESTineTM[25]在生理学上高度相关,但这些模型的吞吐量和寿命往往有限(最长可达6~8 h)。

2. 基于微流控芯片的肠道吸收模型

常规的肠道体外模型缺乏对组织结构的真实模拟、缺乏微生物群,以及肠道功能的复杂性,例如蠕动和流动。随着微流控技术的飞速发展,基于微流控的肠芯片成为了模拟人体胃肠道的有效途径。如图1所示,肠道微环境的关键因素包括肠道的3D绒毛结构、蠕动运动和肠屏障功能等[26]。为了真实地模拟人体肠道,肠芯片模型应能实现以下功能:①通过体外拉伸细胞培养膜来模拟蠕动样运动;②通过控制流体来再现肠道复杂的3D绒毛结构;③通过控制微流体的设计结构和材料的渗透性来产生生理氧梯度:④通过多细胞共培养的方式,研究肠道与其他组织或肠道-微生物之间的互作关系。

图 1 肠道微环境关键特征[26]

图 1 肠道微环境关键特征[26]2.1 肠道芯片设计

在过去的10年中,肠道芯片平台已经从简单的2D结构发展到包括更全面的功能,例如绒毛结构、肠道蠕动、氧梯度,甚至免疫系统。在肠道器官芯片发展的过程中,肠芯片的类型主要分为两种:二维夹膜肠芯片和三维绒毛肠芯片。

二维夹膜肠芯片最常见的设备结构包含两个通道(上部和下部),由半透膜(例如聚碳酸酯或聚酯材料)隔开,在膜上生长的肠上皮细胞形成单层上皮的顶端和基底外侧,这种简单的2D模型通常用于评估药物和营养吸收的体外药动学特性。Kimura等[27]开发了一种集成泵式循环装置和光学检测功能的微流控模型,该模型由被胶原蛋白涂层的半透膜分隔的两层通道组成,以抗癌药物环磷酰胺的渗透评价其吸收功能。Shah等[28]设计了一种基于微流控芯片的人类-微生物共培养模型“人与微生物交互系统”(HuMiX),见图2。培养基灌注微腔室与人肠上皮细胞培养微腔室之间用微米多孔膜(孔径1 μm)隔开,人肠上皮细胞培养微腔室与微生物培养微腔室之间用纳米多孔膜(孔径50 nm)隔开,每个微腔室有独立的进出口,该模型还集成了光电二极管用于监测溶解氧的浓度。2D肠道芯片模型可以模拟肠道细胞上的流体剪切应力,以减少对细胞和培养基的需求,但该模型仍缺乏模拟肠道组织关键特征的功能。

三维绒毛结构的实现对于构建体外肠道模型至关重要,肠道内的绒毛微结构不仅是肠上皮层的生理屏障,更重要的是增加了肠表面的吸收面积。虽然有报道称在平面基质上自发形成绒毛,但缺乏对绒毛尺寸和分布的控制,而且重复性差。微型3D支架的集成已经成为更好地再现人类肠道结构的解决方案。Shim等[29]植入了胶原蛋白支架,以重现肠道组织三维绒毛结构,绒毛高度为300 μm,绒毛间距为150 μm。3D条件下Caco-2细胞增殖良好,均能形成肠屏障。此外,将细胞置于灌注培养的3D培养条件下,可显著提高细胞的代谢活性。Costello等[30]利用激光雕刻翻模的技术制作了一种肠道芯片,在这种芯片中细胞依附于所制作的绒毛生长;但是激光雕刻在模具的制作中有一定局限性。激光雕刻利用激光垂直切割平面基底,制作出的模型多为柱状结构,较难制作出更为复杂的3D模型。张忆恒等[31]通过3D打印技术与表面微结构转移方法,成功地模拟了更为复杂的肠道绒毛。

2.2 流体控制

在肠道中,剪切力在细胞分化中起着重要作用,包括增强黏液产生、增加线粒体活性和提高药物吸收[32]。2D培养时细胞保持在静态条件下,动态参数不容易模拟。在微流控装置中,流体流动可以通过蠕动泵、注射器泵、重力或静水压力以及压力发生器产生,模拟体内液体流动的范围及其在细胞表面的相关剪切应力。与静态条件相比,在连续流动和循环应变下,Caco-2细胞经历细胞分化、极化、绒毛形成、屏障完整性维持、黏液产生等。GOC器件的剪切应力一般取值在0.01 ~ 0.06 dyn/cm2之间,大多数模型中的剪切应力是使用蠕动泵引入的,但这些装置体积庞大且吞吐量低。Tan等[33]用2个微型蠕动泵克服了低吞吐量的限制,每个泵有8个泵管路,允许流体通过16个微通道输送,通过测量微流控芯片中培养的Caco-2细胞氨肽酶活性评估其生长和分化速度,与第21天的静态培养的Transwell系统相比,微流控装置中的Caco-2细胞在第5天显示出更高的氨肽酶活性。尽管该系统具有简单、高通量的特点,但这些模型在重现定义的流速方面是有限的。Kim等[34]开发了一个具有流体流动和施加循环机械应变的肠芯片模型。该装置由两个微通道组成,两侧有两个空心腔室,在空心腔室中施加真空,使分离通道的多孔膜单向延伸。该研究发现,流体流动和周期性机械应变的结合导致了褶皱的形成,这些褶皱再现了肠绒毛的结构,并且该系统中使用的Caco-2细胞显示出极化柱状形态,大小与体内上皮细胞相似。

2.3 机械力刺激

在消化过程中,蠕动是由平滑肌与肠神经系统协同作用,在整个胃肠道内产生的食物的不自主的、周期性的推进。蠕动有助于食物消化、营养吸收和肠排空,但也对上皮产生剪切力和径向压力。研究表明,机械拉伸对于准确模拟人体肠道生理、允许细胞分化和防止细菌过度生长至关重要[35]。Jing等[36]提出并构建了一种基于循环变化流体压差原理的新型蠕动肠模型,通过使用多通道、计算机控制的气动泵同时实现了肠道微系统的流体流动和蠕动,考察了蠕动和流体流动对该装置肠上皮细胞生长和分化的影响。结果表明,微流体装置中的周期性蠕动加上流体流动显著促进了肠上皮细胞的增殖以及糖萼和微绒毛的分泌。此外,肠上皮细胞的屏障、吸收和代谢功能以及细胞分化也受到芯片上周期性蠕动和流体流动的影响。Fang等[37]开发另一款包含200个依次连接的横向微孔阵列芯片,通过调节微孔周围的气道内部气压,从而实现孔内类器官的周期性收缩与舒张,模拟肠道的蠕动。研究结果发现,在蠕动环境中长成的人结肠肿瘤类器官具有更均匀的尺寸分布,对该纳米胶束的摄入量显著降低。Grassart等[38]通过循环拉伸模拟肠道蠕动,研究蠕动状态是否会影响人类志贺菌在3D结肠上皮内的传染性。研究表明,与非机械刺激条件相比,拉伸力(蠕动)的应用显著提高了约50%的感染率,蠕动运动促进了细菌入侵。

2.4 氧气梯度产生

肠上皮富含含氧血液,对于增强绒毛的营养吸收和加速针对病原体的免疫反应至关重要。人体肠道是多种微生物群落的宿主,肠道微生物群在肠道的消化和吸收功能中发挥着重要作用[39]。HuMiX实现了肠道模型中氧气浓度梯度的变化,允许Caco-2细胞和厌氧菌之间的共培养,在体内重现转录、代谢和免疫特征[28]。Shin等[40]开发了一种缺氧-氧气接口(AOI芯片),将缺氧培养基从细菌生长的上通道灌注到肠细胞生长的下通道。实验结果表明,上皮细胞层的存在和管腔微通道中的流量依赖性调节对于在AOI芯片中产生稳态垂直氧梯度是必要且充分的。另一个包含高分辨率溶解氧监测的GOC模型是肠芯片,它有6个传感器盘,在模型的顶部和底部固定有氧淬灭荧光颗粒,允许实时监测氧水平。这种GOC模型有一个中央厌氧室,经常用饱和的5% CO2冲洗,维持上腔内低氧水平。使用这款厌氧肠道芯片,Jalili-Firoozinezhad等[41]也证明厌氧条件比好氧条件在生理上能保持更高的微生物多样性。表1概括了常见的肠道吸收芯片模型及其应用。

表 1 肠芯片模型的主要组成和应用细胞类型 共培养 膜材料 细胞外基质 剪切力 蠕动

(循环机械应变)氧气梯度 应用 Caco-2 否 聚对苯二甲酸(PET)膜 无 1 μl/h 否 否 肠道吸收的功能[42] Caco-2 鼠李糖乳杆菌GG (LGG) 聚碳酸酯(PC)膜 胶原蛋白 25 μl/h 否 是 宿主-微生物分子相互作用[28] Caco-2 人肠微血管内皮细胞 (HIMEC) 聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 否 是 概述疾病模型和对策药物筛选[41] Caco-2 LGG PDMS多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道的运输,吸收和毒性研究[34] Caco-2 大肠杆菌 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道-微生物相互作用和疾病模拟[35] Caco-2 人脐静脉内皮细胞 (HUVEC)、大肠杆菌细胞和巨噬细胞 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白 60 μl/h 15%;0.17 Hz 否 模拟肠道炎症模型和药物筛选[43] 肠道活检类器官 HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 模拟正常肠道生理学[44] 人十二指肠类器官(成人供体) HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物(上皮侧)、Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和纤连蛋白混合物(血管侧) 30 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 研究肠道代谢和药物转运[45] Caco-2 否 无 聚乙烯-醋酸乙

烯酯0.1 ml/min 否 否 高通量药物吸收分析和细菌-宿主相互作用的研究[30] 3. 肠道芯片模型的应用

3.1 肠炎模型的构建

肠炎是一种在发达国家和发展中国家都具有高发病率的疾病,炎症性肠病(IBD)已成为全球性问题,主要包括溃疡性结肠炎和克罗恩病两大类。研究人员发现通过添加细胞因子混合物,例如,白介素-1β、肿瘤坏死因子-α和干扰素γ[46-47],或通过与外周血单核细胞共培养可以在体外模拟肠道炎症[35]。

Kim等[35]在肠芯片中引入致病性大肠杆菌和人单核巨噬细胞构建了相应的肠炎病理模型,并且观察到黏液层损伤、屏障损伤及炎性因子大量表达等炎症反应。之后Shin等[48]又通过在肠腔引入葡聚糖硫酸钠(DSS),首次在体外构建了DSS肠炎损伤及恢复模型,利用该模型作者证明了氧化应激反应是炎症损伤的前提。研究发现蠕动的微流体模型可以重现在小鼠模型中相应的结肠炎,并能观察到的屏障完整性和绒毛结构的破坏。使用来自致病性大肠杆菌的脂多糖激活单核细胞,Caco-2细胞被诱导分泌促炎细胞因子,进而损害屏障完整性,从而模仿IBD病理学特征。此外,促炎信号可以促进中性粒细胞的募集,从而进一步加剧肠道损伤。重要的是,研究人员发现DSS暴露前给予益生菌可以维持肠道屏障,而在DSS后添加细菌时,肠道屏障功能会丧失[49]。这些结果表明,利用体外肠芯片建立肠炎病理模型,可以为肠炎病理机制研究及其治疗药物筛选提供更接近体内肠道环境的研究平台。

3.2 药物吸收和转运

与传统体外肠道模型相比,肠芯片具有高度还原人体肠道微环境、连续的液体流动和高通量筛选的优势[50]。Imura等[42]开发了一种基于微流控芯片的模拟肠道的系统,该芯片由载玻片、半透膜和PDMS组成。以荧光测定结果评价药物渗透性试验,结果显示环磷酰胺能渗透肠屏障,其渗透系数较高,而路西法黄不能在肠壁吸收,其渗透系数较低。这些结果与传统方法的结果一致,证明了该款芯片评估药物吸收的可行性。

Kulthong等[51]分别使用传统的Transwell(静态)和肠芯片(动态)模型,比较高渗透性化合物(安替比林、酮洛芬和地高辛)和低渗透性化合物(阿莫西林)的转运,并使用HPLC或LC-MS测定这些化合物在静态和动态条件下的转运结果。结果显示,相对于静态条件,肠芯片的药物摄取较低,其渗透性值与生物制药分类系(BCS)一致。同样,在接种Caco-2细胞的微流体装置中,几种化合物(姜黄素、甘露醇、葡聚糖、咖啡因和阿替洛尔)的吸收率与体内吸收的研究数据相当。

抗癌药物7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱(SN-38)是伊立替康经羧酸酶转换后的活性代谢物,其抑制拓扑酶Ⅰ的活性远大于伊立替康,但其具有低水溶性和低跨黏膜通透性的缺点。研究人员发现将其合成为亲脂性前体药物能解决低口服生物利用度问题。Pocock等[52]开发了一款基于微流体的肠道芯片(IOAC)模型,该模型可用于研究亲脂性前药的结构-渗透性的关系(见图3)。IOAC模型利用外部机械力作用,诱导上皮细胞单层产生特异性分化,使细胞表面呈现微绒毛表达起伏形态的屏障功能,这比传统的Transwell模型更具生物相似性。用不同链长和不同分子位置的脂肪酸酯修饰SN-38,观察到SN-38前药溶解度与渗透性系数之间有良好的相关性。论证了模仿肠道上皮关键特征的IOAC 模型在筛选亲脂性前药方面具有显著潜力[52]。

图 3 IOAC装置及对难溶SN38和前药的体外渗透系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较[52]A.IOAC装置示意图;B.SN38和前药的体外渗透性系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较;1. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱;2. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-十一酸酯;3. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-10-十一酸酯;4. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-丙酸酯

图 3 IOAC装置及对难溶SN38和前药的体外渗透系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较[52]A.IOAC装置示意图;B.SN38和前药的体外渗透性系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较;1. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱;2. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-十一酸酯;3. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-10-十一酸酯;4. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-丙酸酯4. 结论和展望

近年来,肠道芯片模型在芯片设计、微环境、微流体操控和细胞培养技术方面已经取得了重大进展,为胃肠道疾病机制研究和个体化治疗的发展提供了新的模型。但该技术本身仍然面临许多挑战。

肠上皮细胞的来源对于肠芯片的研究至关重要,Caco-2是目前应用最广泛的模拟肠上皮屏障的细胞系,但Caco-2细胞缺乏黏液生成层,很难控制其分化[53]。此外,Caco-2细胞表现出与人类肠道组织不同的转运蛋白表达[54]。因此,肠芯片还需要进一步研究,以确保上皮细胞系的代谢和转运蛋白活性与在体内观察到的相似。尽管微流控肠芯片模型模拟了人类肠道的许多不同表型和反应,但缺乏在某些疾病中发挥重要作用的特征。例如,平滑肌细胞表达Toll样受体,并且可以通过调节神经胶质源性神经营养因子的产生来调节神经元的完整性。因此,未来的肠道芯片模型构建中应考虑更多因素,例如肌肉和神经系统细胞[20],使得模型具有更多的肠道特征和功能,更接近真实的生理环境。

肠芯片研究的另一个挑战是材料的选用。尽管PDMS在微流控器官装置制备方面具有明显的优势,但PDMS可能吸附介质中存在的小分子、药物或其他荧光标记物,从而降低溶质分子浓度的重现性[55]。为了克服这一点,PDMS及其替代聚合物(例如聚氨酯、苯乙烯嵌段共聚物)的表面改性或基于ECM的材料更适用于预测药物生物利用度或吸收的研究[20]。目前,水凝胶广泛应用于肠道微流控模型,可以提供类似于体内细胞-细胞外基质相互作用的机械和生化环境,促进类组织结构的形成[55]。但其同时存在一些问题,如不稳定、易降解等。因此在未来的肠芯片研究中,寻找开发更优的PDMS替代材料也是非常有必要的。

-

图 1 肠道微环境关键特征[26]

图 3 IOAC装置及对难溶SN38和前药的体外渗透系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较[52]

A.IOAC装置示意图;B.SN38和前药的体外渗透性系数与计算的油-水分配系数比较;1. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱;2. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-十一酸酯;3. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-10-十一酸酯;4. 7-乙基-10-羟基喜树碱-20-丙酸酯

表 1 肠芯片模型的主要组成和应用

细胞类型 共培养 膜材料 细胞外基质 剪切力 蠕动

(循环机械应变)氧气梯度 应用 Caco-2 否 聚对苯二甲酸(PET)膜 无 1 μl/h 否 否 肠道吸收的功能[42] Caco-2 鼠李糖乳杆菌GG (LGG) 聚碳酸酯(PC)膜 胶原蛋白 25 μl/h 否 是 宿主-微生物分子相互作用[28] Caco-2 人肠微血管内皮细胞 (HIMEC) 聚二甲基硅氧烷(PDMS)多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 否 是 概述疾病模型和对策药物筛选[41] Caco-2 LGG PDMS多孔膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道的运输,吸收和毒性研究[34] Caco-2 大肠杆菌 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 30 μl/h 10%;0.15 Hz 否 肠道-微生物相互作用和疾病模拟[35] Caco-2 人脐静脉内皮细胞 (HUVEC)、大肠杆菌细胞和巨噬细胞 PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白 60 μl/h 15%;0.17 Hz 否 模拟肠道炎症模型和药物筛选[43] 肠道活检类器官 HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅰ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物 60 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 模拟正常肠道生理学[44] 人十二指肠类器官(成人供体) HIMEC PDMS膜 Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和Matrigel混合物(上皮侧)、Ⅳ型胶原蛋白和纤连蛋白混合物(血管侧) 30 μl/h 10%;0.2 Hz 否 研究肠道代谢和药物转运[45] Caco-2 否 无 聚乙烯-醋酸乙

烯酯0.1 ml/min 否 否 高通量药物吸收分析和细菌-宿主相互作用的研究[30] -

[1] FITZGERALD K A, MALHOTRA M, CURTIN C M, et al. Life in 3D is never flat: 3D models to optimise drug delivery[J]. J Control Release, 2015, 215:39-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.020 [2] PREKSHA G, YESHESWINI R, SRIKANTH C V. Cell culture techniques in gastrointestinal research: Methods, possibilities and challenges[J]. Indian J Pathol Microbiol, 2021, 64(Supplement):S52-S57. [3] LI X G, CHEN M X, ZHAO S Q, et al. Intestinal Models for Personalized Medicine: from Conventional Models to Microfluidic Primary Intestine-on-a-chip[J]. Stem Cell Rev Rep, 2022, 18(6):2137-2151. doi: 10.1007/s12015-021-10205-y [4] MOYSIDOU C M, OWENS R M. Advances in modelling the human microbiome-gut-brain axis in vitro[J]. Biochem Soc Trans, 2021, 49(1):187-201. doi: 10.1042/BST20200338 [5] HEWES S A, WILSON R L, ESTES M K, et al. In Vitro Models of the Small Intestine: Engineering Challenges and Engineering Solutions[J]. Tissue Eng Part B Rev, 2020, 26(4):313-326. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2019.0334 [6] WALTHER A, COOTS A, NATHAN J, et al. Physiology of the small intestine after resection and transplant[J]. Curr Opin Grastroenterol, 2013, 29(2):153-158. [7] PETERSON L W, ARTIS D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immunehomeostasis[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2014, 14(3):141-153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608 [8] DUTTON J S, HINMAN S S, KIM R, et al. Primary Cell-Derived Intestinal Models: Recapitulating Physiology[J]. Trends Biotechnol, 2019, 37(7):744-760. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.001 [9] VOLK N, LACY B. Anatomy and Physiology of the Small Bowel[J]. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am, 2017, 27(1):1-13. [10] WORTHINGTON J J, REIMANN F, GRIBBLE F M. Enteroendocrine cells-sensory sentinels of the intestinal environment and orchestrators of mucosal immunity[J]. Mucosal Immunol, 2018, 11(1):3-20. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.73 [11] TAYLOR N C, DRAGET K I. Dynamic responses in small intestinal mucus: Relevance for the maintenance of anintact barrier[J]. Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 2015, 95(Pt A): 144-150. [12] FURNESS J B, RIVERA L R, CHO H J, et al. The gut as a sensory organ[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 10(12):729-740. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.180 [13] 王希, 廖吕钊, 江荣林. 肠上皮细胞紧密连接蛋白的结构功能及其调节[J]. 浙江医学, 2018, 40(8):895-898. doi: 10.12056/j.issn.1006-2785.2017.40.8.2017-1901 [14] CANALI M M, PEDROTTI L P, BALSINDE J, et al. Chitosan enhances transcellular permeability in human and rat intestine epithelium[J]. Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 2012, 80(2):418-425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.11.007 [15] 杨巨如. 白术多糖对吊尾大鼠肠道黏膜屏障的防护及机制研究[D]. 哈尔滨:哈尔滨工业大学, 2021. [16] DONALDSON G P, LEE S M, MAZMANIAN S K. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2016, 14(1):20-32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3552 [17] FANG G C, LU H X, AL-NAKASHLI R, et al. Enabling peristalsisof human colon tumor organoids on microfluidic chips[J]. Biofabrication, 2021, 14(1): 015006 FANG G C, LU H X, AL-NAKASHLI R, et al. Enabling peristalsisof human colon tumor organoids on microfluidic chips[J]. Biofabrication, 2021, 14(1):015006 [18] LIU X. Transporter-mediated drug-drug interactions and their significance[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019, 1141:241-291. [19] ESTUDANTE M, MORAIS J G, SOVERAL G, et al. Intestinal drug transporters: an overview[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2013, 65(10):1340-1356. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.042 [20] BEIN A, SHIN W, JALILI-FIROOZINEZHAD S, et al. Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Models of Human Intestine[J]. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 5(4):659-668. [21] LI N, WANG D, SUI Z, et al. Development of an improved three-dimensional in vitro intestinal mucosa model fordrug absorption evaluation[J]. Tissue Eng Part C Methods, 2013, 19(9):708-719. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0463 [22] YU J, PENG S, LUO D, et al. In vitro 3D human small intestinal villous model for drug permeabilitydetermination[J]. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2012, 109(9):2173-2178. [23] ALAM M A, AL-JENOOBI F I, AL-MOHIZEA A M. Everted gut sac model as a tool in pharmaceutical research: limitations and applications[J]. J Pharm Pharmacol, 2012, 64(3):326-336. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01391.x [24] HERRMANN J R, TURNER J R. Beyond Ussing's chambers: contemporary thoughts on integration of transepithelial transport[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2016, 310(6):C423-C431. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00348.2015 [25] STEVENS L J, van LIPZIG M, ERPELINCK S, et al. A higher throughput and physiologically relevant two-compartmental human ex vivo intestinal tissue system for studying gastrointestinal processes[J]. Eur J Pharm Sci, 2019, 137:104989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.104989 [26] DONKERS J M, ESLAMI AMIRABADI H, van de STEEG E. Intestine-on-a-chip: Next level in vitro research model of the human intestine[J]. Current Opinion in Toxicology, 2021, 25:6-14. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2020.11.002 [27] KIMURA H, YAMAMOTO T, SAKAI H, et al. An integrated microfluidic system for long-term perfusion culture and on-linemonitoring of intestinal tissue models[J]. Lab Chip, 2008, 8(5):741-746. doi: 10.1039/b717091b [28] SHAH P, FRITZ J V, GLAAB E, et al. A microfluidics-based in vitro model of the gastrointestinal human-microbeinterface[J]. Nat Commun, 2016, 7:11535. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11535 [29] SHIM K Y, LEE D, HAN J, et al. Microfluidic gut-on-a-chip with three-dimensional villi structure[J]. Biomed Microdevices, 2017, 19(2):37. doi: 10.1007/s10544-017-0179-y [30] COSTELLO C M, PHILLIPSEN M B, HARTMANIS L M, et al. Microscale Bioreactors for in situ characterization of GI epithelial cellphysiology[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1):12515. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12984-2 [31] 张忆恒, 杜静, 夏安越, 等. 基于3D打印技术的微芯片用于模拟肠绒毛和肿瘤表面形貌[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2019, 39(10):1127-1133. [32] DELON L C, GUO Z, OSZMIANA A, et al. A systematic investigation of the effect of the fluid shear stress on Caco-2 cells towards the optimization of epithelial organ-on-chip models[J]. Biomaterials, 2019, 225:119521. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119521 [33] TAN H Y, TRIER S, RAHBEK U L, et al. A multi-chamber microfluidic intestinal barrier model using Caco-2 cells for drugtransport studies[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(5):e197101. [34] KIM H J, HUH D, HAMILTON G, et al. Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinalperistalsis-like motions and flow[J]. Lab Chip, 2012, 12(12):2165-2174. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40074j [35] KIM H J, LI H, COLLINS J J, et al. Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterialovergrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113(1):E7-E15. [36] JING B, WANG Z A, ZHANG C, et al. Establishment and Application of Peristaltic Human Gut-Vessel Microsystem for Studying Host-Microbial Interaction[J]. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2020, 8:272. [37] FANG G C, LU H C, AL-NAKASHLI R, et al. Enabling peristalsis of human colon tumor organoids on microfluidic chips[J]. Biofabrication, 2021, 14(1):015006. [38] GRASSART A, MALARDÉ V, GOBAA S, et al. Bioengineered Human Organ-on-Chip Reveals Intestinal Microenvironment and Mechanical Forces Impacting Shigella Infection[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2019, 26(3):435-444. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.007 [39] MARTINEZ-GURYN K, HUBERT N, FRAZIER K, et al. Small Intestine Microbiota Regulate Host Digestive and Absorptive Adaptive Responses to Dietary Lipids[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2018, 23(4):458-469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.011 [40] SHIN W, WU A, MASSIDDA M W, et al. A Robust Longitudinal Co-culture of Obligate Anaerobic Gut Microbiome With HumanIntestinal Epithelium in an Anoxic-Oxic Interface-on-a-Chip[J]. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2019, 7:13. [41] JALILI-FIROOZINEZHAD S, GAZZANIGA F S, CALAMARI E L, et al. A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip[J]. Nat Biomed Eng, 2019, 3(7):520-531. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0397-0 [42] IMURA Y, ASANO Y, SATO K, et al. A microfluidic system to evaluate intestinal absorption[J]. Anal Sci, 2009, 25(12):1403-1407. doi: 10.2116/analsci.25.1403 [43] JING B, XIA K, ZHANG C, et al. Chitosan Oligosaccharides Regulate the Occurrence and Development of Enteritis ina Human Gut-On-a-Chip[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 10:877892. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.877892 [44] KASENDRA M, TOVAGLIERI A, SONTHEIMER-PHELPS A, et al. Development of a primary human Small Intestine-on-a-Chip using biopsy-derivedorganoids[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1):2871. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21201-7 [45] KASENDRA M, LUC R, YIN J, et al. Duodenum Intestine-Chip for preclinical drug assessment in a human relevantmodel[J]. Elife, 2020, 9:e50135. [46] BEAURIVAGE C, NAUMOVSKA E, CHANG Y X, et al. Development of a Gut-On-A-Chip Model for High Throughput Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(22): 5661. [47] GIJZEN L, MARESCOTTI D, RAINERI E, et al. An Intestine-on-a-Chip Model of Plug-and-Play Modularity to Study Inflammatory Processes[J]. SLAS Technol, 2020, 25(6):585-597. doi: 10.1177/2472630320924999 [48] SHIN W, KIM H J. Intestinal barrier dysfunction orchestrates the onset of inflammatoryhost-microbiome cross-talk in a human gut inflammation-on-a-chip[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115(45):E10539-E10547. [49] GJOREVSKI N, AVIGNON B, GÉRARD R, et al. Neutrophilic infiltration in organ-on-a-chip model of tissue inflammation[J]. Lab Chip, 2020, 20(18):3365-3374. doi: 10.1039/D0LC00417K [50] YEON J H, PARK J K. Drug permeability assay using microhole-trapped cells in a microfluidic device[J]. Anal Chem, 2009, 81(5):1944-1951. doi: 10.1021/ac802351w [51] KULTHONG K, DUIVENVOORDE L, SUN H, et al. Microfluidic chip for culturing intestinal epithelial cell layers: Characterization and comparison of drug transport between dynamic and static models[J]. Toxicology in Vitro, 2020, 65:104815. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2020.104815 [52] POCOCK K, DELON L, BALA V, et al. Intestine-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Model for Efficient in Vitro Screening of Oral Chemotherapeutic Uptake[J]. ACS Biomater Sci Eng, 2017, 3(6):951-959. [53] Edited by VERHOECKX K, COTTER P, LóPEZ-EXPóSITO I, et al. The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: in vitro and ex vivo models[M]. Cham (CH): Springer, 2015. [54] VAESSEN S F, van LIPZIG M M, PIETERS R H, et al. Regional Expression Levels of Drug Transporters and Metabolizing Enzymes alongthe Pig and Human Intestinal Tract and Comparison with Caco-2 Cells[J]. Drug Metab Dispos, 2017, 45(4):353-360. [55] WANG J D, DOUVILLE N J, TAKAYAMA S, et al. Quantitative analysis of molecular absorption into PDMS microfluidic channels[J]. Ann Biomed Eng, 2012, 40(9):1862-1873. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0562-z -

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: