-

溃疡性结肠炎(ulceractive colitis, UC)属于炎症性肠病的一种,有着较高的发病率,其特征为损伤性炎症,近年来有关其病因及发病机制的研究受到广泛关注,但至今仍不明确[1]。对于溃疡性结肠炎的治疗目前多采用手术、抗感染、糖皮质激素及免疫抑制剂等治疗,但上述治疗手段均为对症治疗,且药物长期使用的不良反应很容易造成疾病复发[2]。因此,探究溃疡性结肠炎的发病机制,将为今后治疗药物的研发提供理论基础。

Metrnl(Meteorin-like)是近年来新发现的神经营养因子,也叫Cometin, Subfatin或是IL-39[3-4]。 Jorgensen等[4]在2012年将Metrnl描述为类似于Meteorin(Metrn)的神经营养因子。Metrnl基因开放阅读框包含4个外显子,由936个碱基对编码311个氨基酸。Metrnl蛋白包含45个N端信号肽序列,切除信号肽后的266个氨基酸构成分子量约为30 000的成熟蛋白分子,整个蛋白分子没有穿膜区域,是一种分泌蛋白。到目前为止,关于Metrnl功能的研究较少,我们前期针对该蛋白相关研究确认Metrnl为一种新的细胞因子,阐明了Metrnl通过PPARγ信号通路介导胰岛素的增敏作用的重要机制[5]。 Jorgensen等[4]报道了Metrnl在神经突触生长和成神经细胞迁移中的神经营养活性。Watanabe等[6]报道,Metrnl是潜伏过程(Latent process,LP)基因,可用于细胞分化和神经突触延伸。脂肪组织Metrnl能促进脂肪细胞分化、改善代谢、抑制炎症从而调节脂肪功能,对抗肥胖引起的胰岛素抵抗[7]。通过检测Metrnl在各种组织中的表达,我们发现Metrnl在人和小鼠胃肠组织中,特别是在肠上皮细胞中都高度表达,并发现肠上皮Metrnl敲除后可以通过抑制肠上皮细胞的自噬而加重溃疡性结肠炎,提示 Metrnl是溃疡性结肠炎的治疗靶点[8]。

肠道微环境形成了良好的微生物群栖息地,肠道微生物群被认为是人体的重要器官,越来越多的研究将这种微生物环境与胃肠道疾病联系起来。肠道菌群在溃疡性结肠炎中起着重要作用,如在无菌状态下,无法制备出某些小鼠结肠炎模型(如IL-10缺陷型小鼠等)[9-10]。也有研究报道,在治疗溃疡性结肠炎患者时,联合使用抗生素也显示出了较好疗效[11]。此外,与健康人群相比,溃疡性结肠炎患者的肠道菌群组成也发生了显著变化[12]。但由于人类肠道菌群的复杂性和多样性,目前尚未清楚某些特定菌属与溃疡性结肠炎发病机制的关系。

因此,本研究聚焦溃疡性结肠炎,从肠道微生态角度出发,探究肠上皮Metrnl对于溃疡性结肠炎的作用以及对肠道菌群调节机制的影响。

-

雄性C57小鼠(8周龄,20只,16~20 g),上海西普尔-必凯实验动物有限公司(生产许可证号:SCXK(沪)2013-0016)。Villin-cre小鼠[B6.Cg-Tg(Vil1in-cre)1000Gum/J,021504],2只,16~20 g,美国JAX公司(北京澄天生物科技有限公司代理),生产许可证号:SYXK(京)2018-0016),用于产生肠上皮细胞特异性Metrnl基因敲除小鼠(Metrnl(-/-))。所有小鼠饲养于相对洁净环境下,使用独立通风系统(individual ventilated cages, IVC)动物房,温度恒定(22~26 ℃),室内明暗交替12 h(08:00至20:00照明),相对湿度为40%~70%,笼内维持正压20~25 Pa,每小时换气60~70次。所有实验动物的使用,都经过海军军医大学动物管理机构的同意和认证,符合实验动物饲养及相关管理规定。所有动物实验均按照美国国家卫生研究院实验动物的护理和使用指南进行,并得到海军军医大学动物伦理委员会的批准。IVC系统购自上海鸣励实验室科技发展有限公司。TRIzol试剂(15596026),美国Invitrogen公司;葡聚糖硫酸钠盐(dextran sodium sulfate,DSS),MFCD00081551,分子量36 000~50 000,美国MP公司,引物,生工生物工程有限公司;包埋机(JB- L5,德国徕卡有限公司);切片机(RM2126,德国徕卡有限公司);RT-PCR仪器(ABI 7500系统,美国赛默飞公司);粪便DNA提取试剂盒(QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit,Qiagen, Hilden, 德国);紫外微量分光光度计(NanoDrop 2000,Thermo Scientific, 美国);DNA凝胶回收试剂盒(AxyPrep DNA GelExtraction Kit,Axygen Biosciences, 美国);微型荧光计(QuantiFluor-ST,Promega, 美国);测序仪(Illumina MiSeq,Illumina, 美国)。

-

首先按照本课题组已报道的方法[5]制备Metrnlloxp/loxp小鼠。根据报道的Metrnl(-/-)小鼠的繁殖策略[13],即将Metrnlloxp/loxp小鼠与购买的Villin-Cre小鼠进行交配,产下后代小鼠基因型为Metrnlloxp/wtVillin-Cre。将Metrnlloxp/wtVillin-Cre小鼠和Metrnlloxp/loxp小鼠交配,产生下一代Metrnlloxp/loxpVillin-Cre小鼠。继续与Metrnlloxp/loxp交配,产下的后代,经基因型鉴定分别为Metrnlloxp/loxpVillin-Cre(Metrnl(-/-))和Metrnlloxp/loxp(Metrnl(+/+))。

-

按照本课题组已报道的方法[3],使用TRIzol试剂从肠道组织中提取总RNA,并使用ABI 7500系统进行RT-PCR。最终的20 μl反应混合物包括10 μl SYBR Green,2 μl cDNA模板和1 μl引物。通过重复反应确定平均阈值循环(Ct),将靶基因表达标准化为GAPDH,并使用ΔΔCT方法获得定量测量结果。Metrnl上游引物(F)CTGGAGCAGGGAGGCTTATTT,下游引物(R)GGACAACAAAGTCACTGGTACAG;GAPDH上游引物(F)GTATGACTCCACTCACGGCAAA,下游引物(R)GGTCTCGCTCCTGGAAGATG。

-

雄性C57小鼠(8周龄)于实验室适应2周后,按照本课题组已报道的方法进行模型制备[7],将DSS溶于水中,分别至终浓度为3%和1%,让小鼠自由饮用。

小鼠溃疡性结肠炎疾病程度评分,按照我们之前已报道的的评分标准进行评分[8],对体重下降程度、大便性状、血便情况共3部分分别进行评分,然后进行加和,计算总分数。具体评分标准如下(表1)。

表 1 小鼠溃疡性结肠炎疾病程度评分表

疾病评分 体重下降 (%) 大便性状 大便潜血 0 <1 正常 阴性 1 ≥1-5 - + 2 ≥5-10 软 ++ 3 ≥10-15 - +++ 4 ≥15 腹泻 ++++ 注:“-” 无此性状;“+” 潜血程度。 -

小鼠处死后,取整个结肠部位,测量长度进行比较。然后将结肠下段部位组织用4%多聚甲醛固定,石蜡包埋,切片机切至4 μm的切片,按照之前的实验方法[14],进行HE染色,染色后在光学显微镜下观察炎症细胞浸润情况,组织损伤情况并拍照记录。

-

使用16S核糖体RNA基因测序技术检测肠道菌群。为了进行样品收集和DNA提取,从实验小鼠中收集粪便样品,并在取样后3h内将其冷冻在−80°C下。使用QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit进行DNA提取。使用NanoDrop 2000测量细菌DNA的浓度。然后,将16S核糖体RNA基因测序用于检测细菌DNA。基因的V3-V4区域使用FastPfu聚合酶通过条形码索引引物(338F和806R)进行PCR扩增。然后通过AxyPrep DNA GelExtraction Kit,凝胶提取纯化扩增子,并使用QuantiFluor-ST进行定量。将纯化的扩增子以等摩尔浓度合并,并使用Illumina MiSeq仪器进行末端配对测序。

-

16S rRNA测序数据由Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology平台(V.1.9.1)处理,并进行了MegaBLAST搜索,将生物分类单位的读数(OTU)与国家生物技术信息中心16S rRNA数据库中的参考序列比对。按照文献报道的方法[15]进行宏基因组学分析,从16S rRNA序列推算肠道微生物组的基因组,并且对每个样品的基因含量进行了预测。

-

本实验结果数据以(

$\bar x $ ±s)表示,使用SPSS18.0软件进行统计分析。多组以上比较采用单因素方差分析(One-way ANOVA),各组与正常对照组比较采用Dunnett t检验法,两组比较采用独立样本t检验。以P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。 -

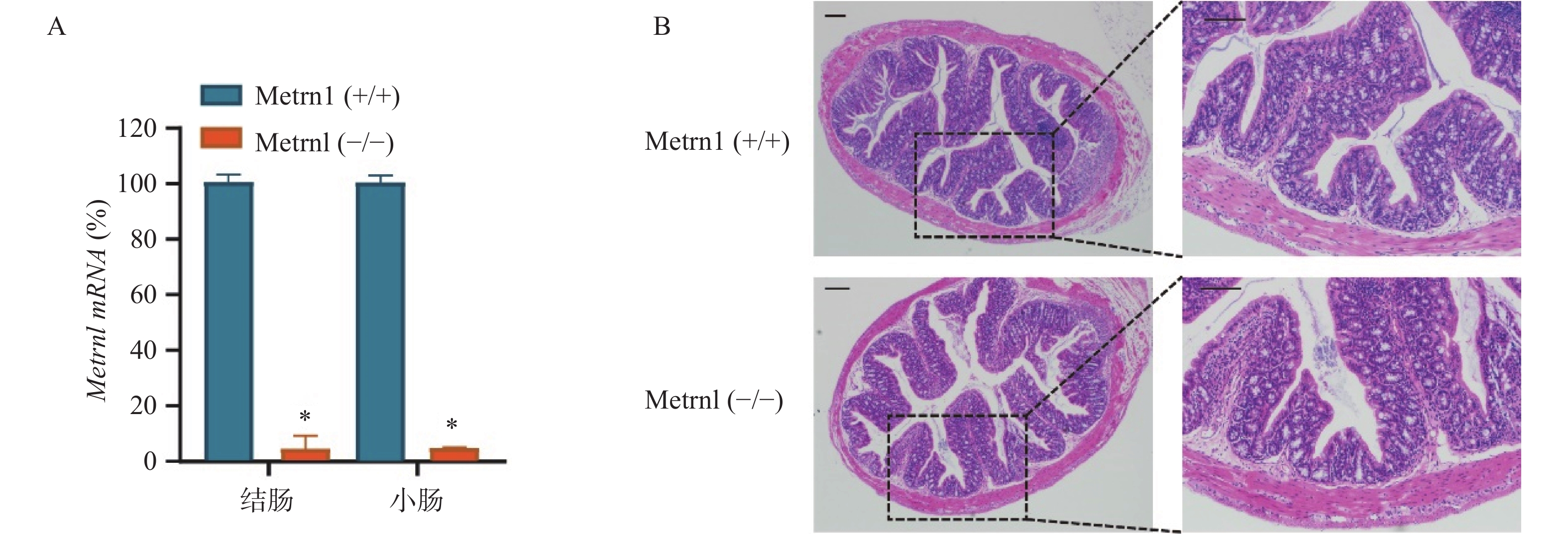

我们构建了肠上皮细胞特异性Metrnl基因敲除(Metrnl(-/-))小鼠,并检测了Metrnl mRNA在大肠和小肠组织中的表达。结果表明,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠中Metrnl mRNA的表达在结肠和小肠组织中极低(图1A)。 HE结肠切片显示Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠之间均无组织损伤和炎症细胞浸润(图1B)。以上结果表明,肠上皮细胞特异性Metrnl基因敲除后不会诱发溃疡性结肠炎。

-

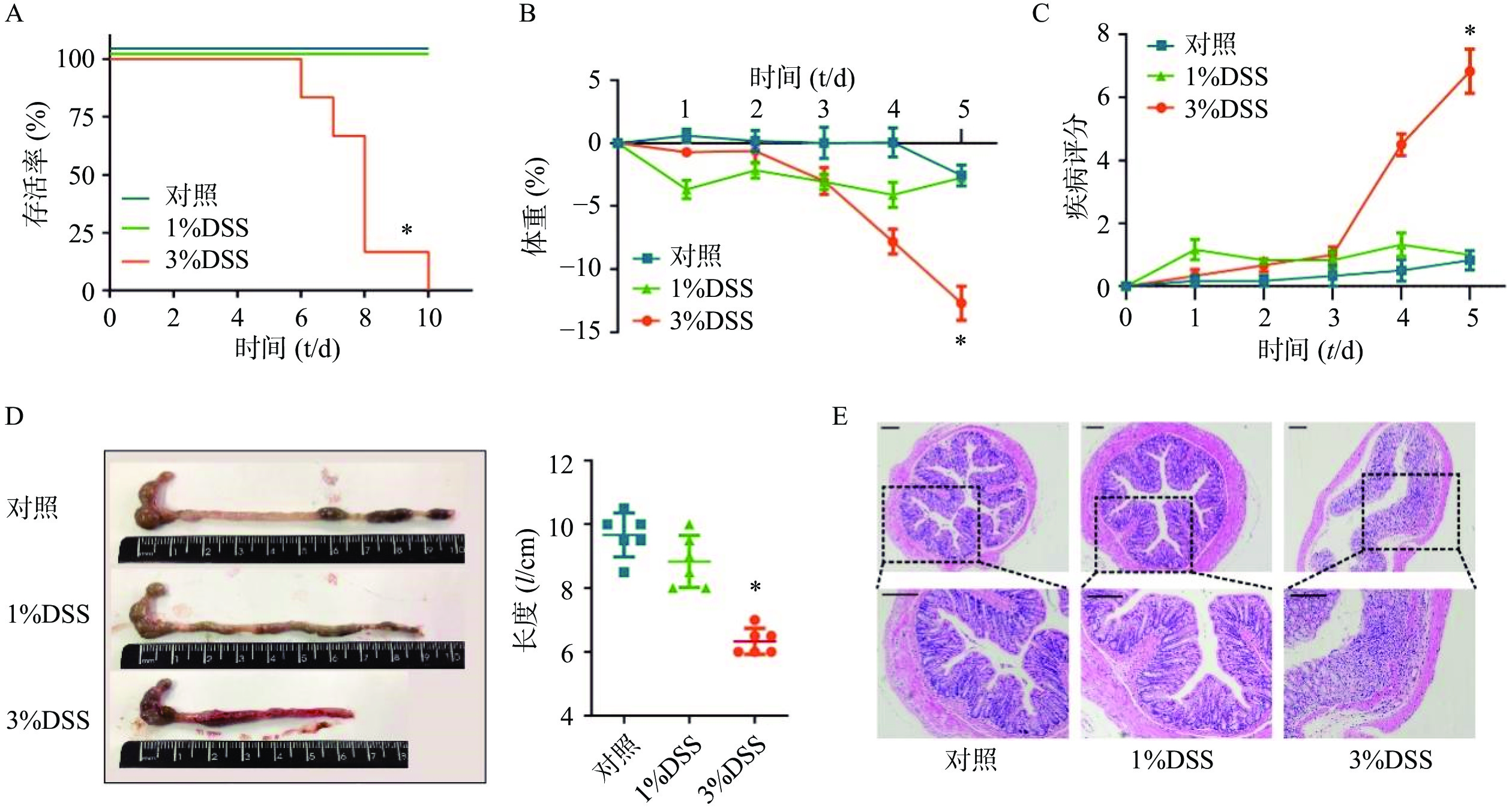

在建立DSS诱发的溃疡性结肠炎模型之前,为了选择最佳的观察时间和DSS给药浓度,我们分别选择3%DSS和1%DSS进行造模,并观察了不同DSS浓度下C57小鼠的存活时间。结果显示,在3%DSS组的第6天,出现了小鼠死亡;直至给药10 d,全部小鼠死亡(图2A)。在1%DSS组中,未观察到小鼠死亡。与对照组相比,3%DSS组的小鼠体重在第5天时显著性降低(P<0.05),而1%DSS组的体重并无显著改变(图2B)。同样,与对照组相比,3%DSS组小鼠DAI增加(P<0.05),结肠长度显著性缩短(P<0.05),而1%DSS组在疾病活动指数、结肠长度方面均无明显变化(图2C-D)。 组织形态学方面,3%DSS组表现出结肠炎表型,具有明显的组织损伤,而对照组并无明显变化(图2E)。因此,我们选择3%DSS和5 d的给药时间作为后续实验条件。

-

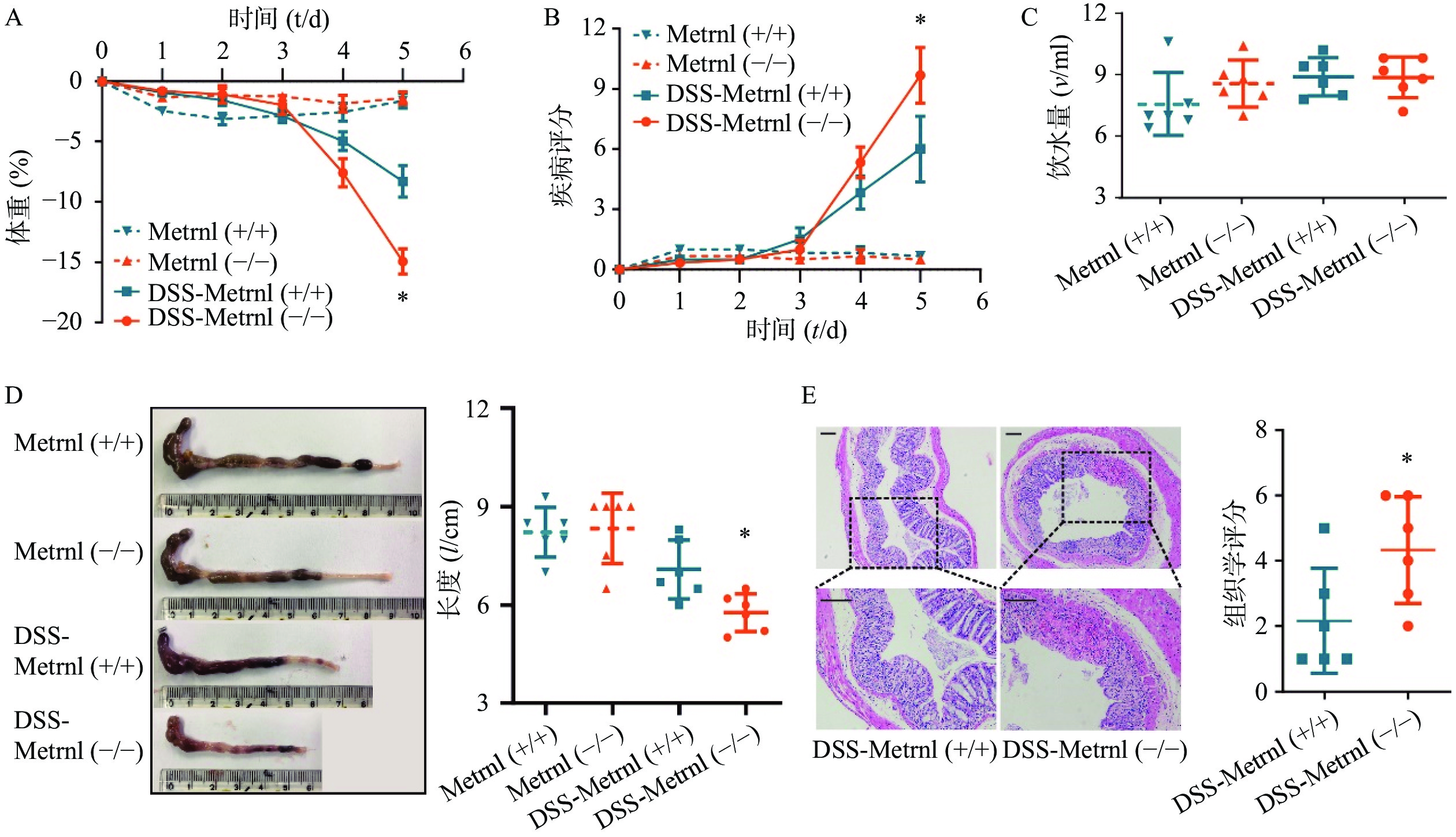

给予Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠3%DSS后,两组小鼠均表现出溃疡性结肠炎症状,其特征为持续的体重减轻、疾病活动指数增加、血性腹泻、结肠长度缩短以及结肠炎症(图3)。在此过程中,在给药后第5天时,与Metrnl(+/+)小鼠体重减轻(−8.27± 1.32)%相比,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠的体重减轻(−14.92±1.05)%,具有统计学差异(P<0.05,图3A);与Metrnl(+/+)小鼠的疾病活动指数(6.00±1.63)相比,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠显著增加至(9.67±1.38)(P<0.05,图3B);与Metrnl(+/+)小鼠结肠长度(7.08±0.89 cm)相比,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠结肠更短(5.77±0.58 cm)(P<0.05)(图3D);为了排除上述差异不是由小鼠摄入不同量的3%DSS引起的,我们还检测了两组小鼠的饮水量。结果显示两组小鼠饮水量之间并无显着差异(图3C)。

-

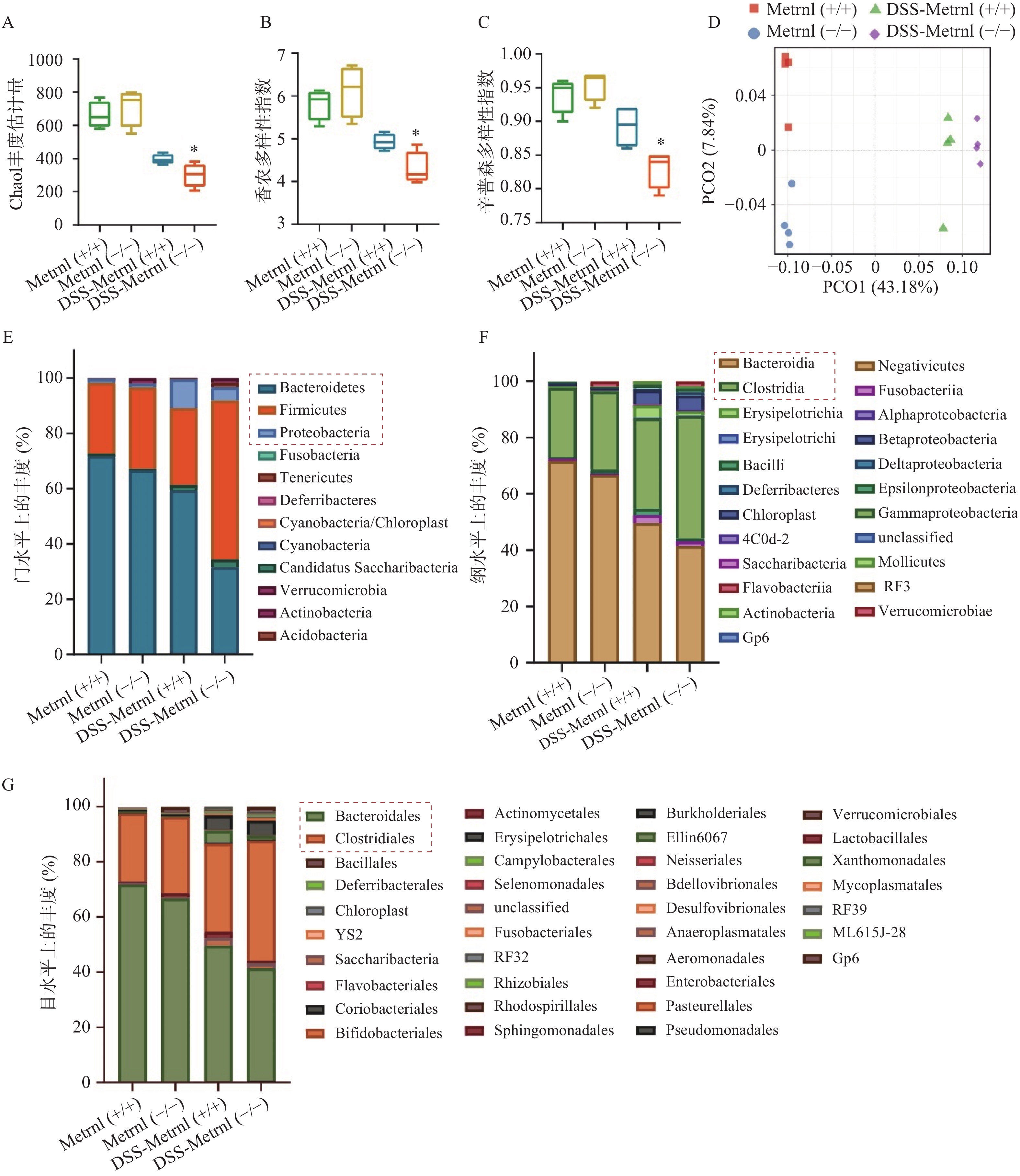

我们通过高通量16S rRNA基因测序,检测了Metrnl对DSS诱导的溃疡性结肠炎小鼠模型中肠道菌群的影响。应用Chao1 丰度估计量(chao1 richness estimator),香农多样性指数(shannon diversity index),辛普森多样性指数(simpson diversity index)三种指标评价各组小鼠中菌群的Alpha多样性(图4A-C)。结果显示,在未进行DSS造模之前,Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠的Alpha多样性并无显著差异;而进行3%DSS造模后,Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠出现了差异,其中Metrnl(-/-)小鼠多样性显著下降(图4A-C)。主成分分析显示,在给予3%DSS造模后的Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠之间微生物的组成显著不同(图4D)。检测小鼠粪便微生物组成,结果显示,在“门”这一层面,给予3%DSS后拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)和变形杆菌门(Proteobacteria)在Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠间存在显著的不同(图4E)。在Metrnl(-/-)小鼠中,Bacteroidetes和Proteobacteria显著降低,而Firmicutes显著升高。在“纲”这一层面,发现给予DSS后,Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠间拟杆菌纲(Bacteroidia)和梭菌纲(Clostridia)具有显著差异。值得注意的是,拟杆菌纲(Bacteroidia)属于拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes);梭菌纲(Clostridia)属于厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)(图4F)。为了进一步探究影响给予DSS后造成Metrnl(-/-)和Metrnl(+/+)小鼠间状态的原因,我们又在“目”层面进行了检测,结果显示(图4G),拟杆菌目(Bacteroidales),属于杆菌纲(Bacteroidia);梭菌目(Clostridiales),属于梭菌纲(Clostridia)发生了显著改变。

-

本研究用DSS诱导溃疡性结肠炎小鼠模型并从对肠道微生物影响的角度出发,探究肠上皮Metrnl特异性敲除对于肠道菌群调节的影响以及对溃疡性结肠炎的作用。发现Metrnl在溃疡性结肠炎小鼠模型中具有保护的功能,该效应可能是Metrnl通过对肠道菌群的调节所致。 近期有一篇关于Metrnl改善克罗恩氏病(CD)的报道,该研究表明肠系膜脂肪组织与肠道存在交互作用,发现小鼠在给予Metrnl后,可通过激活STAT5/PPARγ信号通路,从而达到促进脂肪细胞分化来减轻肠系膜脂肪组织病变的作用[16]。该研究表明Metrnl确实可以影响炎症性肠病的发生发展。除此以外,我们进一步证实了,肠上皮特异性Metrnl敲除后可以加重DSS诱导的溃疡性结肠炎,并且该作用是通过抑制AMPK-mTOR-p70S6K通路,下调了肠上皮细胞自噬水平产生的[7]。

肠道微环境形成了合适的微生物群栖息地,已证明会影响多种消化系统疾病的发生[17]。肠道菌群稳态的紊乱已被广泛认为与炎症性肠病的发病机制和进展密切相关[8]。肠道菌群主要有三种功能,分别是代谢作用,保护作用和营养作用[18-19]。正常人肠道中在“门”这一层面,主要有四类微生物群,包括拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)和变形杆菌门(Proteobacteria)[20-21]。

溃疡性结肠炎的主要特征是有益细菌的减少。拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)是革兰阴性厌氧细菌,构成了哺乳动物胃肠道中主要微生物群[22]。目前认为,拟杆菌门可以通过免疫调节和维持体内平衡而对宿主发挥有益作用。据报道,拟杆菌门可以通过分泌多糖A(polysaccharide A, PSA)来增强抗炎因子IL-10的mRNA表达[23-24]。本研究结果显示出类似趋势,在给予3%DSS进行溃疡性结肠炎造模后,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠症状更加严重,与Metrnl(+/+)小鼠相比,其拟杆菌门的成分显著下降。然而,拟杆菌门在溃疡性结肠炎中并不完全有益。有报道显示,拟杆菌门可以侵入肠道组织并引起个别患者的肠道损伤[25]。因此针对该类菌属的作用还有待进一步验证。除此以外,由于SCFA具有增强肠壁屏障和免疫系统的作用,从而有助于抵抗病原体,因此产生SCFA的菌群目前认为对人体是有益的,例如Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,Roseburia或Eubacterium[26-28]。放线菌门(Actinobacteria)中的双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)也是有益菌群[29-30]。然而,在该属中发现了有争议的结果,因为有研究报道显示,与对照组相比,溃疡性结肠炎患者的Bifidobacterium增加了[31- 32],其原因可能是疾病程度的造成的。因此,需要进一步的研究来阐明该有益菌群在溃疡性结肠炎中的作用。

相反的,目前很多研究显示菌群在溃疡性结肠炎中显著增加,如变形杆菌门(Proteobacteria)下的黏附侵入性大肠杆菌属(adherent-invasive Escherichia coli)和巴斯德杆菌属(Pasteurellaceae),厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)下的韦荣氏球菌属(Veillonellaceae)和瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus gnavus),梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)。我们的研究结果也显示出类似趋势,在给予DSS后,与Metrnl(+/+)小鼠相比,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠的厚壁菌的成分显著上升。除此以外,以下菌属也被认为具有潜在致病性,如大肠杆菌属(Escherichia),沙门菌属(Salmonella),耶尔森菌属(Yersinia),脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio),幽门螺杆菌属(Helicobacter),弧菌属(Vibrio)[31, 33-36]。目前报道较多的是黏附侵入性大肠杆菌,此种细菌能够黏附并穿过肠道黏液屏障,侵入肠道上皮层,促进TNFα分泌和炎症的发生[37-38]。本研究表明,肠上皮特异性Metrnl敲除后,在3%DSS诱导的溃疡性结肠炎模型中,导致肠道菌群动态平衡的进一步紊乱,表明恢复菌群动态平衡对于治疗溃疡性结肠炎至关重要。

需要注意的是,大量研究表明,目前并没有明确具体的哪一种微生物群对人体是有益的,因为每个人的菌群特征都不同。一般而言,只有相对平衡的微生物群,才能最佳地维持人体的代谢和免疫功能以及预防疾病的发展。在健康的肠道中,病原菌和共生菌群可以共存而不会出现问题。但是,这种平衡的任何紊乱都会导致营养不良,从而改变微生物与宿主之间的相互作用[39]。尽管目前普遍认为溃疡性结肠炎中肠环境平衡的破坏是显著发生的,但是造成肠道平衡紊乱的生物学机制的仍然未知,并且不清楚这种紊乱究竟是造成溃疡性结肠炎的原因还是结果。

本研究仍存在不足。首先,肠道微生态对溃疡性结肠炎的保护作用的详细机制仍未探究清楚,特别是肠道中存在的主要4类微生物群(拟杆菌,厚壁菌,放线菌,变形杆菌)对溃疡性结肠炎的作用还有待证实。其次,肠上皮特异性Metrnl敲除后通过调节肠道菌群的组成,从而加重3%DSS诱导的溃疡性结肠炎的作用证据仍不十分充分,需要今后在进一步的研究中加以阐明。

Effect of intestinal Metrnl gene knockout on intestinal microbiota and ulcerative colitis

-

摘要:

目的 探讨肠上皮Metrnl对葡聚糖硫酸钠盐(DSS)诱导的溃疡性结肠炎小鼠模型的作用及其对肠道菌群调节机制的影响。 方法 应用不同浓度的DSS(3%和1%)对C57 小鼠进行造模,确定实验条件。给予肠上皮Metrnl特异性敲除小鼠(Metrnl(-/-))及其对照小鼠(Metrnl(+/+))3%DSS造模5 d,观察模型小鼠的生存时间、体重、疾病评分(DAI)、结肠长度以及结肠组织切片病理学变化等指标。使用16S核糖体RNA基因测序技术检测肠道菌群组成。 结果 与1%DSS相比,3% DSS可显著缩短C57小鼠的生存时间(P<0.05),降低体重(P<0.05),增加DAI评分(P<0.05),缩短结肠长度(P<0.05),增加病理学评分(P<0.05)。给予3%DSS造模5 d后,与对照组Metrnl(+/+)小鼠相比,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠体重下降更多(P<0.05),DAI评分更高(P<0.05),结肠长度更短(P<0.05)以及病理学评分更高(P<0.05)。检测16S核糖体RNA结果显示,Metrnl(-/-)小鼠的肠道菌群多样性下降,拟杆菌(Bacteroidetes)和变形杆菌(Proteobacteria)显著降低,而厚壁菌(Firmicutes)显著升高。 结论 Metrnl对3%DSS诱导的溃疡性结肠炎小鼠有保护作用,该作用可能与Metrnl对肠道菌群的调节作用相关。 -

关键词:

- Metrnl基因敲除 /

- 溃疡性结肠炎 /

- 肠道菌群

Abstract:Objective To investigate the effect of intestinal Metrnl on dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis mouse model and the regulation mechanism of intestinal microbiota. Methods Different concentrations of DSS (3% DSS and 1% DSS) were used to induce ulcerative colitis on C57 mice to determine the experimental conditions. Intestinal epithelial Metrnl specific knockout mice (Metrnl(-/-)) and its control mice (Metrnl(+/+)) were administrated with 3% DSS for 5 d. Then the survival time, body weight, DAI (disease activity index), colon length and pathological changes in colon tissues were observed. 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing was used to detect the composition of intestinal microbiota. Results Compared with 1% DSS, 3% DSS could significantly aggravate ulcerative colitis on C57 mice, such as lower survival rate (P<0.05), more weight loss (P<0.05), higher DAI score (P<0.05), shorter colon length (P<0.05) and higher pathology score (P<0.05). After administrated to 3% DSS for 5 d, comparing with Metrnl(+/+) mice, Metrnl(-/-) mice showed more weight loss (P<0.05), higher DAI score (P<0.05), shorter colon length (P<0.05) and higher pathology score (P<0.05). The 16S ribosomal RNA results showed that the diversity of intestinal microbiota in Metrnl(-/-) mice significantly decreased. Furthermore, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria significantly decreased, while Firmicutes increased. Conclusion Metrnl could protect the DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mouse through regulating intestinal microbiota. -

Key words:

- Metrnl gene knockout /

- ulcerative colitis /

- intestinal microbiota

-

表 1 小鼠溃疡性结肠炎疾病程度评分表

疾病评分 体重下降 (%) 大便性状 大便潜血 0 <1 正常 阴性 1 ≥1-5 - + 2 ≥5-10 软 ++ 3 ≥10-15 - +++ 4 ≥15 腹泻 ++++ 注:“-” 无此性状;“+” 潜血程度。 -

[1] ORDÁS I, ECKMANN L, TALAMINI M, et al. Ulcerative colitis[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9853): 1606-1619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60150-0 [2] MOWAT C, COLE A, WINDSOR A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults[J]. Gut, 2011, 60(5): 571-607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154 [3] LI Z Y, ZHENG S L, WANG P, et al. Subfatin is a novel adipokine and unlike meteorin in adipose and brain expression[J]. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2014, 20(4): 344-354. doi: 10.1111/cns.12219 [4] ROLAND J, Jørgensen, . Cometin is a novel neurotrophic factor that promotes neurite outgrowth and neuroblast migration in vitro and supports survival of spiral ganglion neurons in vivo[J]. Exp Neurol, 2012, 233(1): 172-181. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.09.027 [5] LI Z Y, SONG J, ZHENG S L, et al. Adipocyte metrnl antagonizes insulin resistance through PPARγ signaling[J]. Diabetes, 2015, 64(12): 4011-4022. doi: 10.2337/db15-0274 [6] WATANABE K, AKIMOTO Y, YUGI K, et al. Latent process genes for cell differentiation are common decoders of neurite extension length[J]. J Cell Sci, 2012, 125(Pt 9): 2198-2211. [7] RAJESH R, Rao, . Meteorin-like is a hormone that regulates immune-adipose interactions to increase beige fat thermogenesis[J]. Cell, 2014, 157(6): 1279-1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.065 [8] ZHANG S L, LI Z Y, WANG D S, et al. Aggravated ulcerative colitis caused by intestinal Metrnl deficiency is associated with reduced autophagy in epithelial cells[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2020, 41(6): 763-770. doi: 10.1038/s41401-019-0343-4 [9] ZHANG SL, WANG SN, MIAO CY. Influence of microbiota on intestinal immune system in ulcerative colitis and its intervention[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1674. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01674 [10] KEUBLER L M, BUETTNER M, HÄGER C, et al. A multihit model: colitis lessons from the interleukin-10-deficient mouse[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2015, 21(8): 1967-1975. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000468 [11] Dan, Turner, . Combination of oral antibiotics may be effective in severe pediatric ulcerative colitis: a preliminary report[J]. J Crohn’s Colitis, 2014, 8(11): 1464-1470. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.05.010 [12] QIN J J, LI R Q, RAES J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing[J]. Nature, 2010, 464(7285): 59-65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821 [13] LI Z Y, FAN M B, ZHANG S L, et al. Intestinal Metrnl released into the gut lumen acts as a local regulator for gut antimicrobial peptides[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2016, 37(11): 1458-1466. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.70 [14] HU G, LIU J, ZHEN Y Z, et al. Rhein lysinate increases the Median survival time of SAMP10 mice: protective role in the kidney[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2013, 34(4): 515-521. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.177 [15] TANG R Q, WEI Y R, LI Y M, et al. Gut microbial profile is altered in primary biliary cholangitis and partially restored after UDCA therapy[J]. Gut, 2018, 67(3): 534-541. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313332 [16] ZUO L G, GE S T, GE Y Y, et al. The adipokine metrnl ameliorates chronic colitis in il-10-/ - mice by attenuating mesenteric adipose tissue lesions during spontaneous colitis[J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2019, 13(7): 931-941. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz001 [17] HOOPER L V, LITTMAN D R, MACPHERSON A J. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system[J]. Science, 2012, 336(6086): 1268-1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490 [18] AZIZ Q, DORÉ J, EMMANUEL A, et al. Gut microbiota and gastrointestinal health: current concepts and future directions[J]. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2013, 25(1): 4-15. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12046 [19] SCALDAFERRI F, PIZZOFERRATO M, GERARDI V, et al. The gut barrier: new acquisitions and therapeutic approaches[J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2012, 46 Suppl: S12-S17. [20] SENDER R, FUCHS S, MILO R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body[J]. PLoS Biol, 2016, 14(8): e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533 [21] ARUMUGAM M, RAES J, PELLETIER E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome[J]. Nature, 2011, 473(7346): 174-180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944 [22] WEXLER H M. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2007, 20(4): 593-621. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-07 [23] SARKIS K, Mazmanian, . An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system[J]. Cell, 2005, 122(1): 107-118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007 [24] CHIU CC, CHING YH, WANG YC, et al. Monocolonization of germ-free mice with Bacteroides fragilis protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced acute colitis[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2014, 675786. [25] KUWAHARA T, YAMASHITA A, HIRAKAWA H, et al. Genomic analysis of Bacteroides fragilis reveals extensive DNA inversions regulating cell surface adaptation[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004, 101(41): 14919-14924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404172101 [26] ALAMEDDINE J, GODEFROY E, PAPARGYRIS L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii skews human DC to prime IL10-Producing T cellsthrough TLR2/6/JNK signaling and IL-10, IL-27, CD39, and IDO-1 induction[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 143. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00143 [27] PATTERSON AM, MULDER IE, TRAVIS AJ, et al. Human gut symbiont roseburia hominis promotes and regulates innate immunity[J]. Front Immunol, 2017, 8: 1166. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01166 [28] MUKHERJEE A, LORDAN C, ROSS RP, et al. Gut microbes from the phylogenetically diverse genus eubacterium and their various contributions to gut health[J]. Gut Microbes, 2020, 12(1): 1802866. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1802866 [29] IMAOKA A, SHIMA T, KATO K, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of probiotic Bifidobacterium: enhancement of IL-10 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from ulcerative colitis patients and inhibition of IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14(16): 2511-2516. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2511 [30] ARBOLEYA S, WATKINS C, STANTON C, et al. Gut bifidobacteria populations in human health and aging[J]. Front Microbiol, 2016, 7: 1204. [31] BEN P, Willing, . A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 139(6): 1844-1854. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.049 [32] TAKAHASHI K, NISHIDA A, FUJIMOTO T, et al. Reduced abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria species in the fecal microbial community in crohn’s disease[J]. Digestion, 2016, 93(1): 59-65. doi: 10.1159/000441768 [33] MOUSTAFA A, LI W, ANDERSON EL, et al. Genetic risk, dysbiosis, and treatment stratification using host genome and gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2018, 9(1): e132. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2017.58 [34] KLEESSEN B, KROESEN A J, BUHR H J, et al. Mucosal and invading bacteria in patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with controls[J]. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2002, 37(9): 1034-1041. doi: 10.1080/003655202320378220 [35] GOPHNA U, SOMMERFELD K, GOPHNA S, et al. Differences between tissue-associated intestinal microfloras of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(11): 4136-4141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01004-06 [36] KANG S, DENMAN S E, MORRISON M, et al. Dysbiosis of fecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease patients as revealed by a custom phylogenetic microarray[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2010, 16(12): 2034-2042. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21319 [37] MARTINEZ-MEDINA M, GARCIA-GIL L J. Escherichia coli in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases: an update on adherent invasive Escherichia coli pathogenicity[J]. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol, 2014, 5(3): 213-227. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.213 [38] CHERVY M, BARNICH N, DENIZOT J. Adherent-invasive E. coli: update on the lifestyle of a troublemaker in crohn’s disease[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(10): 3734. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103734 [39] THURSBY E, JUGE N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota[J]. Biochem J, 2017, 474(11): 1823-1836. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510 -

下载:

下载: